Asia is the world’s largest continent. Naturally, this means Asia also has many different kinds of animals living in it. Here we’ve gathered 65 of these intriguing Asian animals for you to know about!

Asian Black Bear

Also known as the Moon bear and the white-chested bear, the Asian black bear has the scientific name Ursus thibetanus. And as its scientific name indicates, the Asian black bear originally came from the Himalayas and remains its primary habitat today. Nonetheless, the Asian black bear is found in surrounding regions such as Southern Iran, Northern India, China, Japan, Taiwan, and even the Russian Far East.

The Asian black bear has average dimensions among bear species, at most growing up to 190 cm and weighing up to 200 kg. It has black fur, but with a distinct white patch on its chest, which may sometimes develop into a v-like shape.

Unfortunately, the Asian black bear has a vulnerable designation for conservation purposes. In particular, the destruction of its native habitats for human development has become the main threat to the bear. Other threats include hunting them for food or to use their various body parts for traditional medicine.

Asian Giant Hornet

The scientific name of the Asian giant hornet is Vespa mandarinia, and its name reflects its status as the world’s largest hornet, with most specimens averaging between 35 and 40 mm in length. In contrast, the European hornet common across the Western Hemisphere only averages around 25 mm in length.

The Asian giant hornet also has a powerful venom by the standards of stinging insects. One victim has described even a single sting feeling like “a hot nail being driven into my leg”. Multiple stings can cause death, as a result of multiple organ failures. Statistics from 2013 show that in China’s Shaanxi Province alone Asian giant hornets killed 41 people and stung an estimated 1,600 people.

Today, Asian giant hornets live widespread across East, South, and Southeast Asia, as well as the Russian Far East. People also first sighted them in North America in 2019, with authorities officially confirming these sightings in 2021. This has led to massive concerns from local governments and scientists alike. They particularly fear that Asian giant hornets becoming an invasive species in North America.

Asian Pipe Snake

These animals actually make up a genus of 13 different species of non-venomous snake, the Cylindrophis. They take their name from their tendency to burrow into the ground, as well as banded patterns over their bodies, which gives them the appearance of a pipe.

Originally widespread across Southeast Asia, Asian pipe snakes have since expanded into Southern China as well as Sri Lanka, but have yet to migrate to the Indian mainland. Given their lack of venom glands, Asian pipe snakes hunt by wrapping their bodies around their prey before squeezing them to death.

That said, scientists know little about Asian pipe snakes, as they tend to avoid people whenever possible. With that, it’s only natural that Asian pipe snake attacks on humans are rare.

Asiatic Lion

The Asiatic lion, with the scientific name Panthera leo leo, once lived across India and the Middle East. Today, however, the Asiatic lion lives only in India. In fact, widespread hunting of their kind since ancient times resulted in their extinction in the Middle East. They also have an endangered designation because of this. As of 2020, scientists estimate that Asiatic lions only have a wild population of around 674 animals.

Compared to their African cousins, Asiatic lions grow to have smaller bodies. On average, they stand around 120 cm high, with a length of 2.87 meters at most. Males also grow smaller manes compared to the males of African lions. That said, records point to Asiatic lions in the past with exception sizes. Emperor Jahangir of Mughal India, in particular, once hunted an Asiatic lion measuring over three meters long in the 1600s.

Bactrian Camel

Also known as the Mongolian camel, the Bactrian camel has the scientific name Camelus bactrianus. Today, it’s widespread in Mongolia, but originally came from the historical region of Bactria, now part of modern Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Compared to the Dromedary camel most commonly associated with the term “camel” in the west, Bactrian camels have two humps. They also have thicker hair, an evolutionary adaptation to the cold and high altitudes of the Hindu Kush Mountains. Bactrian camels also make up the biggest camels in the world, standing around 2.5 meters tall and weighing up to 600 kg.

Bactrian camels is used as pack animals across Asia since ancient times. Merchants particularly used them to carry goods across the Silk Road linking China and Europe.

Bengal Tiger

Also called the royal tiger, the Bengal Tiger has the scientific name of Panthera tigris tigris. It’s also the most iconic tiger species in the world, with most people’s preconceptions of what tigers look like referring to the Bengal tiger.

Its name refers to its home range in the Bengal region of South Asia but the feline has since spread across the continent. Today, Bengal tigers live in Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, and Nepal. Its other name, the royal tiger, also refers to its historical role as a favored pet by Asian rulers and nobility.

Unfortunately, the Bengal tiger today faces various threats to its future, such as hunting and the destruction of its habitats due to human development. With only an estimated 2,500 Bengal tigers left in the wild, international organizations have since designated them an endangered species.

Binturong

Also called the bearcat, the binturong’s scientific name is Arctictis binturong. Its English name refers to how the animal appears to have shared physical characteristics with both cats and bears.

The binturong has a long and heavy body, averaging around 2 meters long and weighing around 24.4 kg. They also have coats of thick black fur, with the fur on their legs having a yellowish tinge.

These animals live widespread across South and Southeast Asia, but a 30% drop in their population since 1980 has led to them becoming a vulnerable species. The cause of this drop primarily revolves around the loss of their native habitat to human development.

Blood Python

With the scientific name Python brongersmai, the blood python takes its name from its distinctive red skin. They feature blotches across their bodies, the colors of which vary from brown to orange, along with black spots along their sides. Their heads are also shaded gray, while their bellies have a white color with black markings.

Like all pythons, blood pythons lack venom glands and hunt by strangling their prey to death. Females also use a similar method to keep their eggs warm, by wrapping themselves around them and then vibrating rapidly, causing heat.

Originally an unpredictable and even aggressive species, widespread domestication of blood pythons has caused them to become more docile. This domestication resulted from either keeping them as pets or growing them to harvest their skins to make leather.

Borneo Elephant

Also known as the Borneo pygmy elephant, with the scientific name of Elephas maximus borneensis, its name indicates that it lives on the island of Borneo, on both the Malaysian and Indonesian sides of the island.

Scientists consider the adjective “pygmy” attached to its name as misleading, born of a misunderstanding before a proper study of this species. The Borneo elephant has the same size as other Asiatic elephants, standing around 2.75 meters tall and weighing around 4 tons.

It officially became an endangered species in 1986 and remains one to this day. Scientists estimate that only 2,000 Borneo elephants live in the wild, around half of their pre-modern population.

Brahminy Blind Snake

With the scientific name of Indotyphlops braminus, this blind snake’s name came from the Indian priestly caste, the Brahmins. It’s also the world’s smallest snake, averaging at most a length of only 4 inches. In fact, this frequently causes most people who see a Brahminy blind snake mistake it for an earthworm, along with its brown color and burrowing behavior.

Scientists aren’t sure whether the species originally came from either Africa or Asia, but it’s widespread in both continents and has even since spread around the world. The Brahminy blind snake also has the rare distinction of a one-gender species, composed solely of females. They support their population with the equally-rare ability of parthenogenesis or sexual reproduction without a male’s involvement.

Bull Shark

With the scientific name of Carcharhinus leucas, it takes its name from its stocky build, wide but flat nose, as well as an aggressive and unpredictable character. In fact, scientists consider the bull shark the most dangerous shark of them all.

It’s also one of the most successful species in the world, having a presence in coastal waters around the globe. That said, it prefers warm tropical waters, limiting its presence in Asia, particularly Southeast Asia, as well as the West Indian and Persian Gulf coasts. It may also travel inland along rivers and other waterways, thanks to its uncommon ability to safely transition between freshwater and marine habitats. Bull sharks can grow up to 2.4 meters long and weigh up to 130 kg.

Burmese Python

With the scientific name Python bivittatus, it takes its name from its native Burma. That said, the species has since spread across Southeast Asia, and thanks to the global exotic pet trade has even reached Florida. However, its presence in Florida has turned the Burmese python into an invasive species.

Burmese pythons make up one of the largest snakes in the world, typically growing up to 5 meters long, with unconfirmed reports of specimens over 7 meters long. As a python, it lacks venom glands of its own, and so uses its body to trap and crush prey to death.

The Burmese python also has a vulnerable designation for conservation purposes. Threats to its future include the loss of habitat to human development, as well as over-hunting for its skin to make into leather.

Caracal

The scientific name of the Caracal is Caracal caracal and its name has Turkish roots, literally meaning “cat with black ears”. Aside from its ears, the rest of the caracal’s body features are either red-brown or sand-colored fur. They typically stand between 40 and 50 cm tall and weigh up to 19 kg.

Today, the caracal has populations across the Middle East and Central Asia. They’ve also migrated to South Asia and even Africa. A territorial animal, they live either alone or in mated pairs, hunting birds and small mammals like rodents. Their wide range of habitats has ensured that the caracal has no threats to its future. In fact, Indians, Iranians, and even Egyptians have tamed the caracal, using them as hunting animals.

Cinereous Vulture

Also known as the black vulture, the monk vulture, and the Eurasian black vulture, it has the scientific name Aegypius monachus. Most of its names refer to its black plumage, while monk vulture comes from how its neck plumage resembles a monk’s cowl.

Cinereous vultures typically grow up to 120 cm long, with a wingspan of up to 3.1 meters from wingtip to wingtip. And with a maximum recorded weight of 14 kg, Cinereous vultures also count as one of the world’s heaviest birds.

They have a wide range of habitats, today living across Central Asia, the Middle East, and most of East Asia as well as parts of Southeast Asia. Southern Europe also features a small population of Cinereous vultures, while in Eastern Europe, they are extinct due to hunting. In fact, hunting remains the biggest threat to their future, with scientists estimating the Cinereous vulture’s total population at only 5,000. They are now near-threatened.

Clouded Leopard

Also called the mainland clouded leopard, it has the scientific name Neofelis nebulosa. They take their name from the black or dark gray cloud-like patterns on their fur, which contrast against the brown of the rest. Clouded leopards also have black stripes that run from their shoulders and down their forelegs. More black stripes run from their eyes over their cheeks, and then down their necks to their shoulders. Clouded leopards typically grow up to 108 cm long, and stand up to 55 cm tall. They also weigh between 11.5 and 23.5 kg on average.

Clouded leopards today have a vulnerable status caused by poaching and the destruction of their habitats. In fact, they’ve since become extinct in places like Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, and even Southern China. Today, they live only in some parts of China, Malaysia, and Thailand, with scientists estimating their total population at 10,000.

Common Krait

Also called the blue krait, it has the scientific name Bungarus caeruleus, with its name referring to its widespread population across South Asia. Its name understates just how dangerous this snake can get, with the common krait actually rivaling the king cobra in terms of lethality. In fact, the common krait makes up one of the Big Four, the deadliest snakes in all of South Asia.

Common kraits have blue or blue-black skin, with up to 40 white bands that fade into simple white spots as the snake grows older. They usually feed on small mammals and other snakes and tend to avoid humans. Unfortunately, common kraits have become so widespread that they inevitably encounter humans, with the snakes biting in response to getting disturbed.

A common krait’s venom acts slowly, so much so that victims typically feel no pain after getting bitten. Within two hours, however, facial paralysis occurs, and within another three hours, the victim loses the ability to breathe. Without prompt medical attention, this results in death from asphyxiation.

Crab-Eating Macaque

Also called the long-tailed macaque, it has the scientific name Macaca fascicularis. It takes its name from its habit of wandering on beaches looking for crabs to eat. They typically grow up to 55 cm tall and can weigh up to 9 kg.

Today, they mostly live in Southeast Asia, as well as in Bangladesh. They’ve also migrated into Southern China as well as Papua New Guinea, however, in both regions, authorities have branded the crab-eating macaque an invasive species.

Crab-eating macaques have a long history with humans, with the animal seen as a sacred animal in its own right in places like Bali in Indonesia, as well as in Thailand and Cambodia. In other places, though, crab-eating macaques have a reputation as pests, from either competing with crab fishermen or feeding off of crops.

In modern times, crab-eating macaques have gained a role as experimental subjects for medical research, particularly in neuroscience and viral studies. This has led to controversy, with animal rights groups calling such treatment inhumane and morally wrong. However, it has also led to key medical breakthroughs, such as American neuroscientist Edward Taub’s development of constraint-induced movement therapy which allows long-term paralysis stroke victims to regain control of their bodies.

Draco Lizard

A genus composed of 40 different lizard species, the Draco lizards stand out from other reptiles with their ability to fly. This results from a set of membranes between their arms and their bodies, which they use to glide through the air over short distances. Scientists have recorded Draco Lizards flying across distances as great as 60 meters.

Carl Linnaeus first studied Draco lizards in the mid-18th century and even gave the genus its name after the reptilian, flying dragons of legend. Surprisingly, it took centuries of research before the scientific community fully accepted the Draco lizard’s ability to fly. In fact, many scientists disputed said ability even during the early 20th century. Most Draco lizards today live in Southeast Asia, with only one species, Draco dussumieri, living in Southern India.

Eastern Black-Crested Gibbon

Also called the Cao-vit black-crested gibbon, it has the scientific name Nomascus nasutus. The name Cao-vit comes from the unique sound it makes, as described by local communities in Northern Vietnam. Aside from Vietnam, the eastern black-crested gibbon also lives in Southern China.

They also have the unfortunate distinction of being a critically-endangered species due to poaching and the loss of habitat to human development. In fact, scientists had already declared them extinct in the 1960s, only to discover small survivor populations in 2002. Even then, the future of the species remains in doubt, with scientists estimating their total population at only 37 animals.

Fattail Scorpion

A genus of 18 scorpion species, the Adroctonus has the distinction of being the biggest and most poisonous scorpion in the world. Its English name refers to how large it is, while the name of their genus literally means “man-killer” in Latin. In fact, statistics estimate that fattail scorpions kill up to 5,000 people around the world every year.

Many of them mostly live in arid areas, such as in the Middle East and North Africa. That said, they’re very adaptable animals and have a presence even in the cold heights of the Himalayas.

Ironically, despite how dangerous fattail scorpions can get, they’re staples of the exotic animal trade. This results from how easy simulating native environments can get for pet fattail scorpions, with simply sun lamps usually enough to provide comfortable heat. Similarly, fattail scorpions aren’t picky eaters, and will happily eat any invertebrates provided for them, such as cockroaches, crickets, and even grasshoppers.

Giant Panda

The most iconic Asian animal of them all, the giant panda rivals the dragon as China’s national symbol. With the scientific name of Ailuropoda melanoleuca, its English name does not actually reflect any difference in size between it and its cousin, the red panda. People simply gave it that name to easily differentiate the two species.

The giant panda typically stands around 1.9 meters tall and weighs up to 125 kg. White fur covers most of its body, with trademark black patches over its ear, eyes, and limbs. Unlike other bears, which have a carnivorous diet, the giant panda is a herbivore. They especially favor bamboo leaves and shoots, which can easily provide 99% of a giant panda’s diet.

Despite its fame, however, human development has put the giant panda’s future in question. This led the Chinese government to place them under protection, while international organizations have designated them a vulnerable species.

Golden Dottyback

With the scientific name of Pseudochromis fuscus, it takes its name from its golden color, making it a popular choice for marine aquariums. That said, the shade of gold can vary depending on the depths the fish originally came from. Golden dottybacks from deep water tend to have brighter scales, while those from shallower water have duller scales.

Scientists have also noted that the fish can adjust the shades of their scales at will, but remain unsure how and why they do it. Golden dottybacks live across the East Indian and West Pacific Oceans — from Sri Lanka to Fiji and from Southern China to Australia.

Gray-Headed Fish Eagle

With the scientific name of Haliaeetus ichthyaetus, it takes its name from the gray plumage on its head, as well as its primarily fish-based diet. Originally native to Southeast Asia, it has since spread to neighboring South Asia countries.

Gray-headed fish eagles typically grow up to 75 cm long and can weigh up to 2.7 kg. Like many other animals on this list, the gray-headed fish has its future threatened by human development. The damming of the Mekong River in Cambodia, in particular, has caused local populations of the bird to drop. While the species currently faces no risk of extinction, between a dwindling population and continued loss of habitat, the gray-headed fish eagle today has a near-threatened conservation status.

Great White Shark

The most iconic shark of them all, great whites come to mind when people hear the word “shark”. Its name comes from its large size, easily reaching up to lengths of around 6.1 meters on average, and weighing up to an estimated 2,300 kg.

Great whites live in both coastal and deep ocean waters around the world, avoiding only freezing Arctic or Antarctic waters. This naturally gives them a presence off of Asia’s long coastlines. With the scientific name of Carcharodon carcharias, scientists unanimously agree that the great white has the role of an apex predator. They have no natural predators, and while scientists have observed them fighting against killer whales, the latter actually avoid great whites whenever possible.

Despite such a status and popular media commonly showing great whites attacking people, they actually keep away from humans. In fact, statistics show that on average great white sharks attack less than 10 people per year.

Greater Flamingo

The biggest and most widespread flamingo species of them all, Phoenicopterus roseus lives across South Asia, the Middle East, as well as Southern Europe, and even Africa. Its name reflects its large size, with greater flamingos easily standing up to 150 cm tall and weighing up to 4 kg.

Despite popular perception, greater flamingos or even just flamingos, in general, don’t always have a deep pink color. In fact, the color only deepens during the mating season. Beyond that, they have a white, pink-tinted color. Chicks get born with dull gray feathers, which slowly lighten as they grow older. Greater flamingos live for a very long time, easily reaching up to 60 years in captivity and 40 years in the wild.

Green Peafowl

Also known as the Indonesian peafowl after its native Indonesia, it has the scientific name Pavo muticus. Unlike other peacocks, both males and females of the green peafowl have large, fan-shaped tails for attracting mates. That said, males of the species lose most of their tail feathers outside the mating season.

Green peafowls also have the distinction of being the longest wild birds in the world, growing up to 3 meters long. Unlike other peacocks, green peacocks can fly, with scientists observing the birds actually prefer to stay in the air as much as possible.

Today, the species has an endangered status because of the destruction of its native habitats and human development. A total population of between 5,000 and 10,000 of the species is what is currently determined.

Hump-Nosed Pit Viper

Also known as Merrem’s hump-nosed viper, it has the scientific name Hypnale hypnale. Its name comes from a hump-like point on its snout, but besides that, it looks like just another viper. The hump-nosed pit viper has gray skin mottled with brown, along with a double pattern of black spots winding down its body. Its belly has a different color, either brown or yellow, with dark mottling, while the snake’s tail has a red or yellow color.

Doctors once considered the hump-nosed pit viper as having mild venom, but have since discovered their mistake. Today, Sri Lanka considers the hump-nosed pit viper the deadliest snake on the island, with a single bite potentially causing death from blood poisoning and kidney failure.

Indian Elephant

Known to scientists as Elephas maximus indicus, this animal comes to mind whenever people hear about Asiatic elephants. Compared to their African cousins, Indian elephants are smaller. On average, they stand between 2 and 3.5 meters and weigh between 2,000 and 5,000 kg. Unlike other elephants, female Indian elephants don’t have tusks.

The Indian elephant has had an endangered status since 1986 after its population fell by 50% over the preceding decades. Scientists found poaching and the loss of habitat as the main cause of this population collapse. Despite official protections extended by the Indian government, both remain serious threats to the Indian elephant’s future.

Indian Peafowl

Also called the common peafowl and the blue peafowl, Pavo cristatus most commonly comes to mind whenever people hear the word “peacock”. Properly speaking, peacocks refer only to males of the species, as females are called peahens. The image most associated with peacocks is a large, slowly-walking bird with a beautiful fan-like tail behind, belonging to males of the species. The females lack this.

Originally native to Southeast Asia, the beauty of the Indian peafowl led to its spread across Asia in ancient times as a status symbol for the rich and powerful. Alexander the Great encountered the Indian peafowl during his conquest of Persia and Northern India, leading to its introduction in Europe.

Today, the Indian peafowl lives in every continent on Earth with the sole exception of Antarctica. It’s also the National Bird of India. With a stable population of over 100,000 animals, the Indian peafowl also has a comfortable least concern conservation status.

Indian Rhino

With the scientific name of Rhinoceros unicornis, the Indian rhino shares its name with its native land. The Indian rhino once roamed freely across the entire subcontinent. Today, however, it lives only in Northern India and Southern Nepal. Poaching and destruction of its habitats have caused its population to collapse, with scientists estimating only 3,600 Indian rhinos left in the wild. Of those, an estimated 70% live in India’s Kaziranga National Park.

Indian rhinos have the distinction of being the world’s second-largest rhinos, standing around 186 cm tall with a length of 380 cm. They also weigh around 2,200 kg. This also makes them the second-largest land animals in Asia, after the Asiatic elephants.

Indochinese Tiger

Indochinese tigers actually share the same scientific name as the Bengal tiger. Scientists still remain unsure whether or not they represent two different species, with only circumstantial evidence supporting the difference between them. In particular, Indochinese tigers have darker fur as well as smaller bodies. Indochinese tigers can grow up to around 285 cm long and can weigh up to 195 kg.

They mostly live in Thailand, with small groups wandering to and from neighboring Laos and Myanmar. Much like Bengal tigers, Indochinese tigers have an endangered species designation, with scientists estimating only 342 of them are left alive in the wild.

Japanese Macaque

One of the most iconic monkeys in the world, they’ve become famous for pictures of bathing in Japan’s many hot springs. Other names of theirs include Macaca fuscata, as well as the snow monkey, the latter referring to how many live in permanently-snowy areas. In fact, no other monkey in the world lives in such northern latitudes as the Japanese macaque.

Their widespread population across Japan has also given them a close relationship with the Japanese people. The famous samurai, Kato Kiyomasa, for example, historically kept a Japanese macaque as a pet. They also feature in some Japanese legends, such as that of the hero Momotaro, as well as the folk tale The Crab and the Monkey.

In Japanese religion, the thunder god Raijin kept Japanese macaques as his companions. Most famous of all are the Three Wise Monkeys who proclaim “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil”.

Javan Rhino

Also known as the Sunda rhino or the lesser-horned rhino, it has the scientific name Rhinoceros sondaicus. Most of their names refer to their origin, such as the island of Java in Indonesia, itself part of the greater Sunda Archipelago. The name lesser-horned rhino refers to its horn, the smallest out of all rhinos in the world. At most, their horns grow up to only 27 cm, compared to 36 cm for the horns of Indian rhinos. Javan rhinos also grow smaller than their Indian cousins, reaching a maximum height of only 1.7 meters. That said, they can also grow heavier than their Indian cousins despite their smaller size, weighing up to 2,300 kg.

Today, the Javan rhino has a critically-endangered status, with scientists estimating at most only 100 animals left in the wild. Poaching and loss of habitat remain the biggest threats to their survival, but the war has also left its mark on the species. The brutal and bloody Vietnam War and other Communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia during the late 20th century unintentionally inflicted massive losses on the species. Other threats to their future include inbreeding, as their small population has forced surviving Javan rhinos to mate with close relatives. This led scientists in 2018 to begin genetic studies in the hopes of finding a solution before the Javan rhino’s situation worsens.

King Cobra

The most famous snake in the world and one of the most venomous, the king cobra is a member of the Big Four, a collection of the deadliest snakes in South Asia. In fact, unlike other snakes which bite quickly before retreating just as quickly, the king cobra has a habit of holding its bite for as long as possible. At the same time, it constantly pumps venom into its victim, which contributes to the animal’s lethality. A king cobra can pump out 450 mg of venom in a single bite, enough to paralyze a person and kill them by asphyxiation. Medical statistics point to 60% of all untreated king cobra bites as resulting in death.

Unsurprisingly, this lethality has made the king cobra symbolic of death and destruction in Indian mythology. This, in turn, has helped make the king cobra the national reptile of India.

The king cobra also has the distinction of the longest venomous snake in the world, easily growing up to 5.85 meters long. It also has a distinctive appearance, with a retractable neck flap or hood which it spreads as a warning against anyone that approaches. The king cobra comes in various colors, ranging from black to shades of brown. Black specimens also feature white bands going down their bodies.

Despite its widespread presence in South and even Southeast Asia, the king cobra counts as a vulnerable species. In particular, the destruction of its habitats for human development not only threatens its future but forces it into circumstances where it comes into potentially-violent contact with humans.

Kinabalu Giant Red Leech

With the scientific name of Mimobdella buettikoferi, it takes its name from Malaysia’s Mount Kinabalu, the one place in the world the leech lives in. The name also refers to its size, with the Kinabalu giant red leech growing up to 50 cm long. It also has a red-orange color, likewise referenced in its name.

Despite its status as a leech, the Kinabalu giant red leech does not feed on blood, unlike other leeches. Instead, it feeds on other worms, such as earthworms, and as such mostly stay underground. In fact, the Kinabalu giant red leech usually only appears on the surface after heavy rains. By being saturated with water, the leech surfaces for air.

Koi

The Cyprinus rubrofuscus is one of the most famous fish in the world. Its fame comes from its rich colors, making many of them popular additions to Japanese fishponds. Their name also has dual meanings, for both carp and love.

Scientifically speaking, Koi refers to domesticated breeds of the Amur carp widespread across East and Southeast Asia. Koi come in many colors, deliberately bred to develop those colors for aesthetic purposes. These include black, blue, brown, cream, orange, red, white, and yellow. The most expensive koi even come in metallic shades, such as gold and even platinum.

Komodo Dragon

With being ferocious predators, scientists consider Komodo dragons the apex predators of their home island Komodo in Indonesia. Part of their fame also comes from their evolutionary link to the now-extinct dinosaurs. Also known as Komodo monitors, they have the scientific name Varanus komodoensis.

Komodo dragons can grow up to 3 meters long and weigh up to 70 kg. They live and hunt in groups, something recognized by scientists as a rarity among reptiles. They also have a rare kind of venom, still partly a mystery to science, but which seems to work by destroying the victim’s blood.

Despite their fame and dominance, a combination of human development and climate change has reduced them to endangered species. This has led the Indonesian government to place them under protection, but even that can only go so far, given the global nature of climate change.

Malayan Tiger

Like the Indochinese tiger, scientists still remain unsure about whether or not the Malayan tiger represents a separate species from the Bengal tiger. Circumstantial evidence does exist, though, with the Malayan tiger having a smaller body than the Bengal tiger. They typically grow up to 259 cm long, with a height of up to 104 cm and weight of up to 88 kg.

Malayan tigers once ranged over what would become modern Malaysia, as well as Singapore Island. Today, however, Malayan tigers only live in small parts of Eastern and Northern Malaysia. They also live in parts of Southern Thailand. No Malayan tigers live in Singapore today, with the last ones hunted to death in the 1950s. Scientists estimate that, at most, only 120 Malayan tigers remain in the wild today. This forced the Malaysian government to put them under protection in the hopes of preserving the species.

Markhor

Also called the screw-horned goat, it has the scientific name Capra falconeri, with its English name referencing its screw-shaped horns. Markhor, however, comes from the Urdu language in Pakistan, itself derived from the animal’s name in Classical Persian. Pakistan itself considers the Markhor as its national animal.

Markhor today lives in the mountain ranges of Central Asia, as well as on the slopes of the Himalayas. Many of them feed on the leaves of mountain scrub trees, while they are hunted and preyed on by local predators. These include snow leopards, wolves, and even golden eagles. Markhor typically grows up to a length of 186 cm and weighs up to 110 kg.

Only poaching makes up any real threat to their future, with the Markhor’s native habitats haven’t been reached by human development. That said, poaching has taken its toll on their population, leaving them a near-threatened species.

Mekong Giant Catfish

With the scientific name Pangasianodon gigas, it once held the world record for the world’s biggest freshwater fish. It can grow up to 3 meters long and weigh up to 350 kg. In fact, the Mekong giant catfish still holds the world record for the largest freshwater fish ever caught, for a specimen that is 2.7 meters long and weighing 239 kg.

The fish’s name references its home waters in the Mekong River, which starts from Tibet and flows through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam to the sea. This has made it vulnerable to human development and now the Mekong giant catfish is a critically-endangered species. Scientists estimate that the species’ population has dropped by 80% since the industrialization of the region where it lives began.

Monitor Lizard

A genus composed of 80 different reptile species, the Varanus has a widespread presence across South and Southeast Asia. They are also spread beyond those regions, into Africa, Australia, and even North America.

They are most commonly associated with the famous Komodo dragon. The Komodo dragon makes up the extreme upper range of the genus, with most monitor lizards averaging only around 1.5 meters long. Some of them can get very small too, with a length of only 20 cm. Most of them also live as solitary animals, again unlike the Komodo dragons which commonly represent the genus.

That said, they share many similarities, from similar body builds to a carnivorous diet. They’re also all venomous, with the various monitor lizards each having a different kind of venom of their own.

Philippine Eagle

Also known as the monkey-eating eagle or the Philippine great eagle, it has the scientific name Pithecophaga jefferyi. Its names refer to either its Philippine homeland or to its habit of hunting and preying on various monkey species. It’s also the third-largest eagle in the world, growing up to 102 cm long with a weight of up to 8 kg.

Both the eagle’s size and predatory habits have made it the apex predator and the national bird of the Philippines. Ironically, the Philippine eagle has suffered heavily from the Philippines’ development, particularly the destruction of rainforests and jungles. This has reduced them to being a critically-endangered species and forced the Philippine government to place them under protection.

Red-Crowned Crane

Also called the Japanese crane or the Manchurian crane, it has the scientific name Grus japonensis. Its name refers to a patch of dark red on top of its head, which lightens to bright red during mating season. This crown vividly contrasts with the rest of the crane’s body — white plumage and black wing feathers. Males also have black feathers on their cheeks and necks.

Ironically, despite their association with Japan, most red-crowned cranes live on the mainland. They spend spring and summer in either Manchuria or the Russian Far East. They then migrate to Korea or Southern China for autumn and winter. That said, the red-crowned cranes living in Japan do not migrate, and instead spend the whole year in the country.

Reticulated Python

With the scientific name Malayopython reticulatus, it takes its name from the net-like pattern of its multicolored scales. The color scheme of these patterns generally follows an irregular theme of light-colored scales surrounded by dark-colored scales. This results in what scientists call disruptive coloration, which makes the reticulated python effectively invisible in forest environments.

The reticulated python is the longest snake in the world and the largest snake in Asia. It can grow up to lengths of 6.5 meters and weigh up to 75 kg. This made the reticulated python a popular exhibit in zoos worldwide. Given its large and widespread population across South and Southeast Asia, the reticulated python currently faces no threats to its continued existence.

Russell’s Viper

This snake has the scientific name Daboia russelii and takes its name from Patrick Russell, who first described the animal in 1796. Russell’s viper can grow up to 166 cm long and weigh up to 10 kg. Its upper body comes in various colors, ranging from brown to yellow with a pattern of dark brown spots running down its length. In contrast, its belly typically has a white or even pink color, with irregular patterns of dark-colored spots.

Russell’s viper also has a place in the Big Four, the deadliest snakes in South Asia. A single bite delivers on average around 70 mg of venom, enough to kill a person. The venom works by literally destroying body tissues, with the victim starting to bleed from the gums and even vomiting blood within 20 minutes of the bite. Muscles around the bite die almost immediately, which could result in long-term complications without medical assistance. Death also usually results in a day without medical assistance, resulting from either blood poisoning, kidney failure, or even cardiac arrest.

Russian Sturgeon

Also called the Danube sturgeon or the diamond sturgeon, it has the scientific name Acipenser gueldenstaedtii. Its name refers to the country it most commonly lives in, the rivers and other freshwater bodies of Russia, but it’s also widespread across Central Asia and Eastern Europe. The Caspian Sea also features a large population of Russian sturgeon.

People don’t usually eat Russian sturgeon despite its edible status, but it’s commonly fished as the source of a famous Russian delicacy: caviar. Unfortunately, Russian sturgeon aren’t especially prolific and take a long time to mature. Together with the high demand for caviar, the Russian sturgeon is left a critically-endangered species.

In an effort to preserve the species while also accommodating economic realities, Russian scientists launched an effort to crossbreed the Russian sturgeon with other fish. It met its first success in 2020 when they crossbred a Russian sturgeon with an American paddlefish. The resulting sturddlefish grow much faster than Russian sturgeon, but it remains unclear if their eggs prove suitable as commercial caviar.

Saiga Antelope

With the scientific name Saiga tatarica, the Saiga antelope once lived across the Eurasian landmass from Mongolia in the east to Romania in the west. This made it a staple source of meat for the nomadic people of the Eurasian steppes. Archaeologists have found evidence of humans hunting Saiga dating back to the 5th century B.C. In fact, Saiga antelopes continue to get hunted for their meat today in Kazakhstan, despite an official ban on the hunting of the animal. The animal’s horns also have value in traditional medicine, especially in China.

This, however, has contributed to the species’ decline starting at the end of the 20th century. Ironically, the Soviet Union proved the Saiga antelope’s greatest protector, with a stable population of 2 million animals within its borders. Following its collapse, however, the Saiga antelope’s population fell by 95% over the next 15 years. Today, the Saiga antelope has the status of a critically endangered species, with only small groups of the animal left in Southern Russia, Central Asia, and Mongolia.

Saltwater Crocodile

Also called the Indo-Pacific crocodile, or the marine crocodile, it has the scientific name Crocodylus porosus. It takes its name from its habitat in coastal waters and river mouths, as well as its ability to swim in the ocean. This makes it unique from other crocodiles, which live in freshwater and avoid the ocean as much as possible. This also allowed the saltwater crocodile to expand from its native Eastern India across all of Southeast Asia and even reach Northern Australia.

The saltwater crocodile also has the status of an apex predator with no predators of its own. More than that, they even prey on other apex predators like the great white shark. Its body reflects the power to back this status, with saltwater crocodiles able to grow up to 6 meters long and weigh up to 1,300 kg.

Saw-Scaled Viper

A genus of twelve venomous viper species, the Echis take their name from the saw-like arrangement of their scales. Saw-scaled vipers mostly live in South Asia, but they’ve also expanded to the neighboring Middle East and North Africa. The kind of venom of each species varies, with some species having paralyzing neurotoxins. Others have blood-destroying hemotoxins, heart-stopping cardiotoxins, or even tissue-destroying cytotoxins.

The amount of venom a saw-scaled viper surprisingly depends on the season and the gender. Scientists have since discovered that males usually have more venom than females. Saw-scaled vipers also have more venom in the dry season than in the rainy season.

Siberian Tiger

Also called the Amur tiger, it technically remains the same species as the Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris. That said, while not distinct enough to count as a separate species, scientists have confirmed that the Siberian tiger has different genes from the Bengal tiger. Scientists aren’t completely sure how and when they diverged from each other, but they think the link lies with the now-extinct Caspian tigers. Siberian tigers also grow larger than Bengal tigers, easily growing up to 208 cm long and weighing up to 212 kg.

Once widespread across Korea, Northern China, and Mongolia, the Siberian tiger now lives only in the Russian Far East. In both modern and pre-modern times, hunting remains the main threat to the species, with its fur valued as a luxury good. This led the Russian government to strictly enforce protections for the animal. As of 2015, scientists estimate only 562 Siberian tigers are left in the wild.

Sloth Bear

Also called the labiated bear, it has the scientific name Melursus ursinus, and takes its common English name from its particularly long claws. These claws have a similar appearance to those of sloths, and also give the sloth bear similarly-excellent climbing abilities. Labiated bear, in contrast, comes from the animal’s long lower lip and mouth structure. Both make the sloth bear very good at sucking up insects for food.

Sloth bears have an average size for bears, standing up to 92 cm tall and weighing up to 145 kg. They live across most of South Asia, with Bangladesh as the exception. Hunting by humans led to their extinction in the mentioned country and made them a vulnerable species. While local governments have placed them under protection as a result, this has come under fire from many people for pragmatic reasons.

In particular, sloth bears make up the most aggressive bears in the world. Sloth bears attack more humans than any other kind of bear. This led to people protesting about their inability to protect themselves from a sloth bear’s attack. Or if they do, they fear getting charged with animal cruelty or even poaching in the aftermath.

South China Tiger

Also called the Amoy tiger, controversy has surrounded its nature in the early 21st century. Max Hilzheimer originally classified them as Felix tigris amoyensis in 1905, differentiating them from the Bengal tiger based on the difference in their skulls. However, in 2017, a scientific review dismissed this difference as superficial and merged them with the Bengal tiger. This came under fire in 2018, after a genetic study proved that the South China tiger has a distinct genetic pattern of its own.

In fact, many scientists theorize the South China tiger as the original tiger from which all other tigers evolved from before the last Ice Age. The controversy continues to this day, sadly overshadowing the fact that the South China tiger has become extinct in the wild. Today, the only South China tigers all live and breed in captivity. This has also left a serious question of how long the species can last before they completely go extinct.

Sri Lankan Elephant

Known to scientists as Elephas maximus maximus, the Sri Lankan elephant sets the standard against which other Asiatic elephants get compared. Its English name, in turn, refers to its native Sri Lanka, and the only place where the animals live today.

The Sri Lankan elephant has a smaller size than the African elephant, standing up to 3.5 meters tall and weighing up to 5,500 kg. Only males have horns, but not all males grow them for reasons not yet understood by scientists.

Sri Lankan elephants also have an endangered status, as a result of poaching, loss of habitat to human development, and even war. In particular, statistics estimate that up to 300 elephants died from landmines and other conflict-related injuries between 1990 and 1994 alone.

Sumatran Elephant

Its scientific name is Elephas maximus sumatranus and it reflects its native island of Sumatra in Indonesia. Sumatran elephants typically grow up to 3.2 meters tall and weigh up to 4,000 kg. They also have the lightest skin tones out of all Asiatic elephants.

Sumatran elephants currently have a critically-endangered status, as a result of poaching and human development of their habitats. Their decline lasted over three decades, falling from 4,800 animals in 1985 to only 2,800 animals by 2007. In fact, they’ve become locally extinct in Western Sumatra, and stand at risk of similarly going extinct in Northern Sumatra. In an effort to preserve the species, the Indonesian government hasn’t simply placed them under protection but has even tried to herd the species into special reserves.

Sumatran Orangutan

With the scientific name of Pongo abelii, their name references their native island of Sumatra in Indonesia. Compared to other orangutans, Sumatran orangutans have thinner bodies and longer faces, with similarly longer and brighter hair. Typically, they stand up to 1.7 meters tall and can weigh up to 90 kg.

Hunting originally did not pose a threat to the Sumatran orangutan, with the species only coming under the threat of extinction in the 21st century. This resulted from the global surge in demand for palm oil. This, in turn, led to vast areas of rainforest getting cleared for palm tree plantations. By 2017, the species’ population had dropped to an estimated 15,000 animals in Northern Sumatra, earning them a critically-endangered species.

Even before that, in 2014, a new threat emerged when an orangutan suffered a strep throat infection, which previously only affected humans. Most concerningly for medical experts attempts to treat the orangutan with standard antibiotic treatments failed. The reason for the failure remains unclear, but scientists study the incident seriously. In particular, they fear a potential mutation that could similarly render antibiotics ineffective in treating strep throat in humans.

Sumatran Tiger

Unlike most other Asian tigers, the Sumatran tiger retains its scientific name of Panthera tigris sondaica. This resulted from a genetic study in 1998, which proved the Sumatran tiger distinct from the Bengal tiger and its various branches across Asia.

The Sumatran tiger once stood as only one of several tiger species scattered across the Sunda Archipelago. These included the Bali tiger, as well as the Javan tiger, both of which have since gone extinct.

Today, the Sumatran tiger remains the only tiger species in the Sunda Archipelago, on their home island of Sumatra. Poaching and the destruction of their native habitat, particularly to make way for palm tree plantations has left the Sumatran tiger a critically-endangered species. Scientists estimate that at most the Sumatran tiger has only around 700 animals left in the wild.

Sunbeam Snake

A genus composed of two snake species, the Xenopeltis take its name from its iridescent scales that break down incoming light into various colors. Sunbeam snakes aren’t venomous, and like pythons, they hunt by wrapping around their prey to crush them to death. Sunbeam snakes, however, do have a relationship with pythons. Their bodies reflect this, with sunbeam snakes having long and powerful bodies, averaging around 1.3 meters long.

Sunbeam snakes live across Southeast Asia, but only in the wild. Attempts to keep them in captivity have failed, with the snakes finding it too stressful and dying quickly as a result. Scientists have even discovered they don’t take getting handled by people well at all, with some even dying out of the resulting stress.

Sun Bear

With the scientific name of Helarctos malayanus, sun bears take their name from a circular, cream-colored patch on their chest. Sun bears have the distinction of the bears who live mostly on trees. This has also given them distinctively-long claws which help them climb trees and avoid falling down. Sun bears also count as the world’s smallest bears, having a height of at most 70 cm, a length of 140 cm, and a weight of 65 kg.

They mostly live in Southeast Asia. However, both Bangladesh and Northern India also have small populations of sun bears. Poaching and the loss of habitat both threaten their future, while also driving sun bears into confrontations with humans that end with casualties on both sides. The sun bear is currently vulnerable.

Sunda Pangolin

People know pangolins as scaly anteaters, or simply as anteaters. As referenced by its name, Sunda pangolins come from the Sunda archipelago of Southeast Asia. These include the countries of Indonesia and Malaysia, but Sunda pangolins also have a presence on the mainland. They also have the scientific name of Manis javanica.

Like other pangolins, the Sunda pangolin has large and powerful claws that let it tear into ant and even termite nests. Their fur protects them from attempts by the insects to fight back, while its long and sticky tongue literally lets it suck them all up.

The Sunda pangolin poses no threat to people whatsoever and even tries to avoid them as much as possible. Unfortunately, Sunda pangolins have long suffered from traditional medicine demanding their various body parts. Together with the destruction of their habitats, the Sunda pangolins are left a critically-endangered species.

Ironically, this demand for Sunda pangolin parts in traditional medicine may have helped start the COVID-19 pandemic. A study in 2020 found viruses in Sunda pangolin parts in Southern China with a 99% similarity to the original COVID-19 strain. This, in turn, led to an intensified investigation of the exotic animal trade in China.

Taimen Salmon

Also called the common taimen, or the Siberian taimen, it has the scientific name Hucho taimen. Taimen itself refers to a wide variety of edible fishes widespread across East Asia and the Russian Far East. As its name indicates, the Taimen or Siberian salmon originally comes from Siberia but has become widespread across Russia. It’s also one of the biggest edible fishes in the country and a staple source of meat.

Taimen salmon can grow up to 180 cm long and weigh up to 30 kg. Despite their widespread population, overfishing has put the species under serious strain in recent decades. The Taimen salmon currently counts as a vulnerable species, leading the Russian government to tighten fishing regulations.

Tarsier

A family of 14 species divided into three genera, the Tarsiidae include some of the most iconic primates in Southeast Asia. These include the Philippine tarsier, which features on the country’s 200 PHP banknote.

Tarsiers generally have small bodies, averaging at most a length of only 12 cm and a weight of 160 grams. They also have very large eyes compared to the rest of their bodies, at most up to 16 mm across. This actually makes a tarsier’s eyes bigger than its brain.

Based on fossil evidence, scientists have discovered tarsiers have generally retained the same physical features over the last 45 million years. This also makes them some of the oldest mammals in the world, with a presence across Asia, Europe, and even North America. Today, though, they only live in the jungle habitats of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Tiger Shark

Its scientific name is Galeocerdo cuvier and its English name is from the tiger-like stripes on its sides. These stripes fade, however, as the shark ages, with the oldest tiger sharks having near-invisible stripes as a result.

As powerful predators, tiger sharks have the widest range of prey out of all sharks in the world. These include birds, dolphins, fish, sea snakes, shellfish, squid, turtles, and even other sharks. Their predatory habits have caused them to commonly get featured in popular media as mankillers. In truth, tiger sharks attack even fewer humans than great white sharks.

If anything, humans prey on tiger sharks instead, with their fins an ingredient in various shark fin dishes. This has actually resulted in tiger sharks becoming a near-threatened species. This, in turn, has forced governments worldwide to strictly regulate the fishing of the animals.

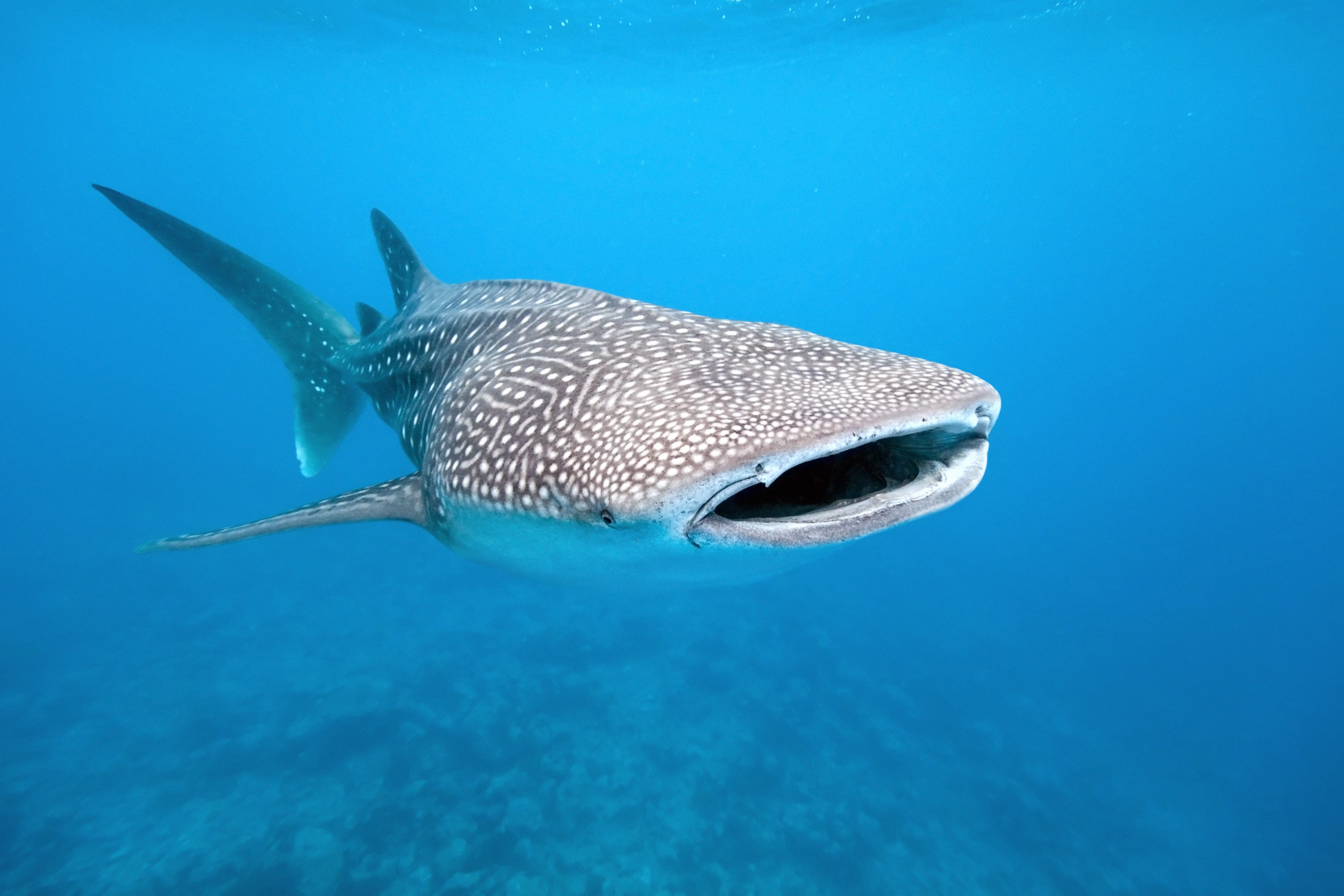

Whale Shark

The whale shark, with the scientific name Rhincodon typus, is not only the world’s largest fish but also the world’s largest vertebrate. On average, they grow up to 10 meters long and weigh up to 19,000 kg.

Despite their huge size, and the inclusion of “shark” into their name, whale sharks also have the reputation of being the world’s gentlest animals. They pose no threat to people, even avoiding ships whenever possible. Younger whale sharks even display playful attitudes towards any divers they encounter. Whale sharks feed only on plankton and small shrimp and fish, which they filter from the water through the pads in their mouths.

Sadly, industrial pollution and accidental collisions with ships have taken their toll on the whale sharks. While scientists still struggle to give an exact number of whale sharks in the world today, international organizations have branded them as endangered species to protect them from further losses.

White-Bellied Heron

Also called the Imperial heron, Ardea insignis takes its English name from its white belly. This contrasts with the rest of the bird’s plumage, which mostly has a dark gray color except for its neck and the back of the head, which have silver feathers. They also count as the world’s second-largest herons, standing up to 127 cm tall and weighing 3.4 kg.

They once lived in the wetlands of South and Southeast Asia, but today live only in Myanmar, as well as parts of India and Bhutan. This resulted from the destruction of said wetlands, usually from human development. Scientists estimate that the white-bellied heron now numbers only 300 animals at most, making them a critically-endangered species.

Yak

The iconic beast of burden in the Himalayas also goes by the Tartary ox and Bos grunniens. The name “yak” itself comes from Tibetan, where it properly refers only to males of the species. The females are called “bri” or “dri”. In addition to the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, yaks also live in parts of Myanmar and Pakistan. Both Mongolia and Russia also have sizable populations of yaks inside their borders.

Scientists have studied the yak’s genes and discovered they split off from modern cows between 1 to 5 million years ago. In particular, they feature unique evolutionary adaptations to the cold and thin air of their mountain homelands. These include bigger and stronger hearts and lungs, as well as a different kind of hemoglobin. That said, these adaptations also make them unsuitable for warmer regions. Yaks actually suffer from heat-related problems at average temperatures of above 15 degrees Celsius.

A yak’s size varies with the breed, but yaks on average stand around 138 cm tall and weigh around 585 kg. Their milk and meat provide staple food for the people in the Himalayas, while their fur also provides a source of workable cloth. Even their droppings have an important role for Himalayan peoples, specifically as fuel. In fact, in treeless parts of the Himalayas, yak droppings form the only fuel source available.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.