The Mayan civilization is one of the most fascinating ancient cultures in history, known for its remarkable achievements in various fields, including astronomy, mathematics, and architecture. Here are 50 facts that highlight the richness and complexity of the Mayan culture, spanning from their daily life to their mysterious decline.

1. Advanced Mayan Calendar

The Mayans developed a complex calendar system that was more accurate than the modern Gregorian calendar. It played a crucial role in their religious and agricultural practices.

2. The Heart of Central America

The Mayan civilization thrived in what is now Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and parts of Honduras, making it a central aspect of Central America’s history.

3. Architectural Marvels

Mayans built impressive pyramids and cities like Chichen Itza and Tikal, which stand as a testament to their architectural genius.

4. The Mayan Empire

At its peak, the Mayan empire boasted a large population across numerous city states, each with its own ruler and god patrons.

5. Unique Writing System

The Maya developed their own hieroglyphic writing system, which was used to record their history, achievements, and religious rituals.

6. Pioneers in Astronomy

Mayan astronomers could predict solar eclipses, and their long count calendar was used to track vast periods of time.

7. The Mesoamerican Ballgame

The Mesoamerican ballgame was not just a sport but a religious activity. Players could only use their hips to hit the ball.

8. Advanced Mathematics

The Mayans invented a number system that included the concept of zero, an advanced mathematical concept not present in many contemporary cultures.

9. Importance of Corn

Corn was a staple in the Mayan diet and played a significant role in their mythology and daily life.

10. The Sacred Cenotes

Cenotes, natural sinkholes, were considered sacred in Mayan culture and were often used for sacrificial rituals.

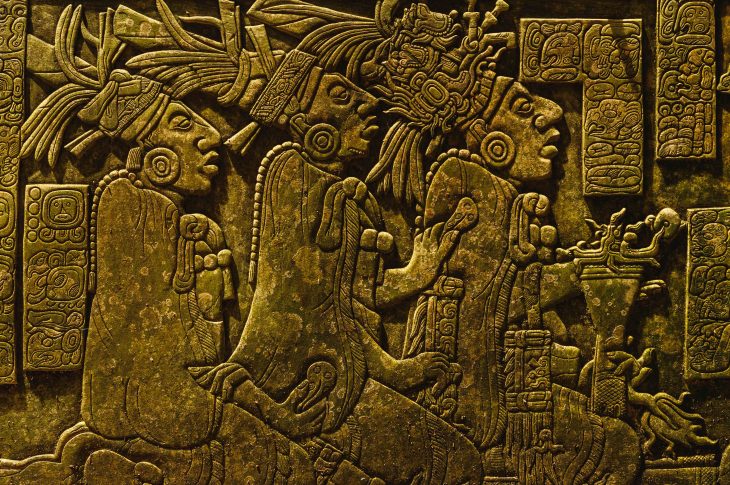

11. Skilled Artists

Mayan artists were highly skilled in pottery, sculpture, and painting, often depicting deities, rulers, and scenes of everyday life.

12. The Feathered Serpent

The feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, was one of the most important gods, symbolizing wisdom and wind.

13. Human Sacrifice

Human sacrifice was a part of Mayan religion, believed to appease the gods and maintain cosmic balance.

14. Mayan City States

The Mayan city states were fiercely independent but linked through trade routes and alliances. Tikal and Calakmul were among the largest city states.

15. Classic Period

The Classic Period (250-900 AD) was the height of the Maya civilization, marked by great artistic and intellectual achievements.

16. Elaborate Costumes

During religious rituals, participants wore elaborate costumes and masks to embody gods or mythical creatures.

17. The Spanish Conquest

The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century marked the end of many Mayan cities through disease, warfare, and forced conversion.

18. The Mystery of Their Decline

The mysterious decline of the Maya during the ninth century is still debated, with theories ranging from drought to constant warfare.

19. Natural Medicine

Mayans utilized a vast knowledge of medicinal plants and practices, including sweat baths for purification and healing.

20. The Post-Classic Period

Following the Classic Period, the Post-Classic Period saw the rise of powerful cities like Mayapan and the increased influence of the Aztecs.

21. Skilled Astronomers

Archaeological evidence shows that Mayans were skilled astronomers, meticulously observing celestial bodies and recording their movements.

22. The Mayan Religion

Mayan religion was polytheistic, with a vast pantheon of gods related to elements of the natural environment.

23. Ingenious Agriculture

Mayans created sustainable farming methods, including slash-and-burn agriculture and terracing to support their large population.

24. The Importance of Jade

Jade was highly valued in Maya society, used in jewelry, as currency, and in burial rites for the Maya nobility.

25. The Codices

Only a few Mayan books, or codices, survive today, offering precious insights into Maya culture, astronomy, and rituals.

26. The Monkey Dance

The Monkey Dance is a traditional Mayan performance that combines dance, music, and costumes to tell stories from their mythology.

27. Social Hierarchy

Maya society had a complex social hierarchy, with the Maya nobility at the top, followed by priests, warriors, artisans, and farmers.

28. The Potter’s Wheel

Unlike many ancient civilizations, the Maya did not use the potter’s wheel, yet they produced intricate ceramics and pottery.

29. Trade and Economy

The Mayan economy was heavily based on trade routes connecting different city states and regions, trading goods like jade, cocoa, and feathers.

30. Chocolate Innovators

The Maya were among the first to cultivate cacao, using it to make a frothy chocolate drink for religious ceremonies and as a luxury item.

31. The Mayans and the Aztecs

While the Mayans and Aztecs are often mentioned together, they were distinct civilizations with their own cultures, although the Aztecs did pay tribute to Mayan achievements.

32. Hierarchical Warfare

Warfare was a means to gain territory, captives for sacrifice, and prestige. It was deeply entwined with religious practices and social status.

33. Unique Beauty Standards

Beauty standards in Mayan culture included flattened foreheads, crossed eyes, and jade inlaid teeth.

34. The Ballgame Continues

The ancient Mesoamerican ballgame is still played today in modified forms in some parts of Central America.

35. Calendar Systems

Besides their famous Long Count calendar, the Maya used own calendars for agricultural and religious purposes.

36. The Concept of Time

For the Maya, time was cyclical, not linear, influencing their worldview and religious rituals.

37. Writing on Tree Bark

The Mayans wrote on tree bark paper, creating codices that were unfortunately largely destroyed during the Spanish conquest.

38. Hallucinogenic Drugs

Hallucinogenic drugs were used by Mayan priests to induce visions and communicate with the gods during rituals.

39. Tattoos and Body Modification

Tattoos and body modifications were common, reflecting social status, achievements, or religious devotion.

40. Astronomy and Architecture

Many Mayan cities and buildings were aligned with astronomical events, like solstices and equinoxes, showcasing their deep understanding of the cosmos.

41. The Classical Period

The Classical Period was marked by the development of powerful city states and significant advances in Mayan culture.

42. Agriculture and the Environment

The Mayans had a profound respect for the natural environment, which influenced their agricultural practices and religious beliefs.

43. Mayan Gods

The pantheon of Mayan gods included deities associated with elements of nature, agriculture, and war.

44. Daily Life

Daily life for the Maya varied greatly depending on social status, but most engaged in farming, trading, and participating in community and religious activities.

45. Religious and Ceremonial Life

Religious and ceremonial life was central to Maya culture, with rituals, dances, and ceremonies performed to honor gods and ancestors.

46. The Importance of Black Beans

Black beans were a staple food, providing essential nutrition and featuring in many traditional dishes.

47. Education and Training

Nobles and future priests received formal education in writing, mathematics, and astronomy, while others learned trades and farming techniques.

48. The Influence of the Maya

The Maya civilization’s influence extends far beyond its historical period, impacting modern culture, science, and art.

49. The Great Civilization

The Maya were a great civilization not just for their monumental architecture but for their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and sustainable living.

50. Legacy and Continuation

The descendants of the ancient Mayans still live in Central America, maintaining many aspects of their ancestors’ culture, language, and traditions.

Final Word

This list of 50 Mayan facts barely scratches the surface of the depth and breadth of the Mayan civilization, a testament to the enduring legacy of one of the world’s most fascinating ancient cultures.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.