Elizabeth Peratrovich is well-known for her efforts towards the first anti-discrimination law in the United States in 1945. Together with her husband Roy, they fought to win recognition and equality for the Native Alaskans in their home state. This happened even before the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s finally earned its place. Learn more about this amazing woman with these Elizabeth Peratrovich Facts.

- Alaska celebrated February 16 as Elizabeth Peratrovich Day since the year 1988.

- The Alaska House of Representatives has also named one of their galleries in her honor.

- Anchorage also has a park named in her and her husband’s honor.

- Ketchikan’s Southeast Alaska Discovery Center named their theater in Elizabeth’s honor as well.

- The National Women’s History Project named her as an honoree for 2018’s Women’s History Month.

- Elizabeth Peratrovich came into the world on July 4, 1911, in Petersburg, Alaska.

- From birth, she was a member of the Lukaax̱.ádi Clan of the Tlingit Nation’s Raven moiety.

- As a Tlingit, she had the name Ḵaax̲gal.aat, meaning Person who Packs for Themselves.

- She gained the name Elizabeth Jean after getting orphaned and then adopted by Andrew and Jean Wanamaker.

- She married Roy Peratovich in 1931.

- Between 1934 and 1942, they had three children: Roy Jr., Frank, and Loretta.

- While living in Juneau in the 1940s, the family experienced widespread discrimination against Alaskan natives.

- The family spent some time in Canada, and then Oklahoma, before moving back to Alaska.

- While in Canada, Elizabeth’s husband Roy earned an economics degree from St. Francis Xavier University.

- Elizabeth died in 1958 from breast cancer.

- Elizabeth Peratrovich has an award named after her by the Alaska Native Sisterhood.

- Her civil rights campaign became the focus of a 2009 documentary, For the Rights of All: Ending Jim Crow in Alaska.

- In 2019, The New York Times gave her an obituary as part of the Overlooked No More series.

- Elizabeth Place in Anchorage is an apartment named in her honor.

- Petersburg received a mural in Elizabeth’s memory in 2020.

Elizabeth Peratrovich’s husband started out working in a fishery in Klawock.

But he didn’t stay there indefinitely, instead of going into politics. In fact, before moving to Juneau, Roy Peratrovich ran for mayor and won four terms in office.

Elizabeth and her husband began their activist career in 1941.

Discrimination against Native Alaskans spurred them on, particularly signs outside various establishments barring dogs and natives inside. They even found themselves refused a lease on a house after the owner discovered they were natives themselves. This led Elizabeth and Roy to band together with other activists and proposed an anti-discrimination bill before the Alaskan State Congress. However, Congress voted it down in 1943. Even then, they refused to give up.

They both continued to work in government offices at this time.

Elizabeth, in particular, worked in the territorial treasury, as well as for the legislature. She also spent some time working for the Juneau Credit Association.

At the same time, they held leadership positions in native organizations.

Elizabeth, in particular, held the office of Grand President for the Alaska Native Sisterhood. As for her husband, Roy held the same office for the Alaska Native Brotherhood.

Alaska Governor Ernest Gruening held sympathy for their movement.

In fact, even before Elizabeth began her activist career, Gruening had publicly shown disapproval of the widespread discrimination in his state. He even used his personal influence to convince several communities to end the practice of segregating white and colored people. He also supported Elizabeth and her colleagues’ bill in the state congress but could do nothing in 1943 when the state congress voted it down.

Elizabeth testified before the Alaskan Senate in 1945.

She did so to try and get another anti-discriminatory bill through the state congress. Her testimony led Senator Allen Shattuck to describe her and her fellow natives as people barely out of savagery. The senator then contrasted them to whites, who had 5000 years of civilization behind them. Elizabeth simply pointed out that 5000 years of civilization or not, the Bill of Rights applied to all citizens equally. Elizabeth’s testimony shamed the opposition, helping the bill pass a vote in the Alaskan Senate. From there, it went to the governor’s office, with Gruening signing it into law on February 16, 1945. This made Alaska the first state to abolish official racial discrimination since the late-19th century.

Elizabeth’s sons have also continued their mother’s legacy.

Roy Jr. became a civil engineer in adulthood, and later designed Juneau’s Brotherhood Bridge, named in honor of the Alaskan Native Brotherhood. Frank, for his part, later became the Juneau Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Tribal Operations Officer.

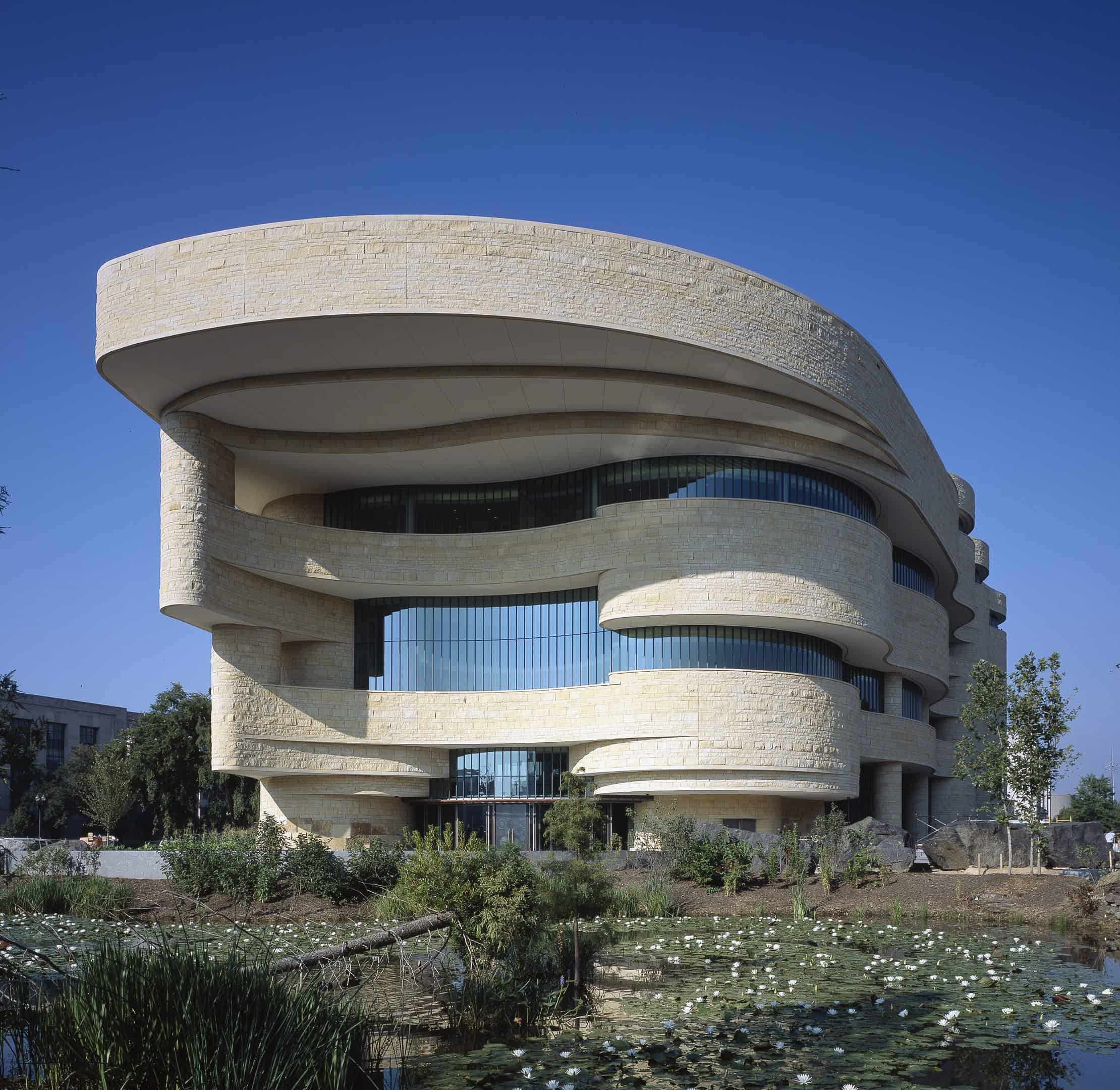

The Smithsonian Institute also preserves the material legacy of Elizabeth’s work.

Specifically, the National Museum of the American Indian branch of the institute does. They keep all of the Peratrovich family’s written materials connected to their activism, from letters, personal notes and research, and even newspaper clippings. In doing so, they help to preserve their legacy for future generations.

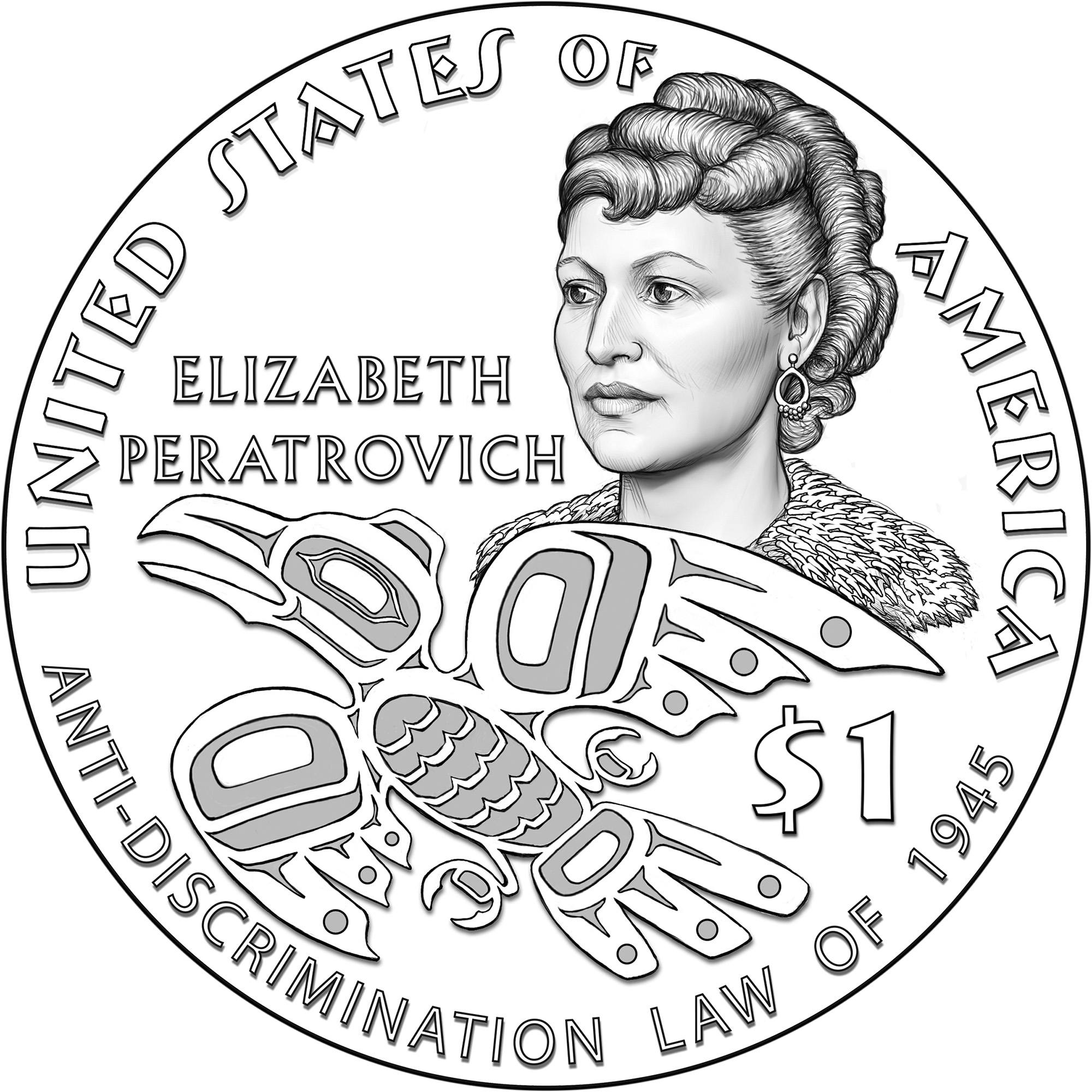

The US Mint later commemorated Elizabeth with a special $1 coin.

They first announced it in October 2019, with Elizabeth featuring on the back of the coin. This makes her the first Native American to appear on US money, with the first coins entering circulation in February 2020. The US Mint plans to release a total of five million coins of the design, available online.

2020 has seen other commemorations of Elizabeth’s legacy.

In January, Elizabeth became one of the 20for2020 highlights of extraordinary achievements by women. Later that year, on December 30, Google Doodle released in Canada and the USA a special artwork by Michaela Goade honoring Elizabeth.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.