As the last native civilization to rise in Central Americas, the Aztecs were Spain’s first encounter in the New World. Because of this, much has been twisted in terms of Aztec history. Find out what Aztec heritage really means and set the record straight with these Aztec facts.

- At its largest, the Aztec Empire covered an area of 220,000 km².

- The Aztec Empire ruled over 5 to 6 million people at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

- The Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had a population of at least 140,000 people at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

- The Aztecs had their own calendar, based on a solar cycle of 365 days.

- The Aztecs worshipped over 200 gods, each ruling over one domain of life, the world, or the cosmos.

- The Aztecs began migrating into Central Mexico from the north sometime before the 10th century.

- They settled in the Tizapan region in 1299, only to get expelled by Colhuacan soon after.

- The Aztecs founded Tenochtitlan in 1325.

- Tenochtitlan was a vassal of Azcapotzalco until 1426.

- In 1426, Tenochtitlan formed an alliance with Texcoco and Tlacopan against Azcapotzalco.

- Azcapotzalco’s defeat in 1428 marks the beginning of the Aztec Empire.

- Emperor Moctezuma I established Aztec power during his reign from 1440 to 1469.

- The Aztec Empire expanded from the Mexico Basin and into the surrounding region over the course of the late-15th century.

- The Spaniards arrived in Mexico in 1519.

- The Aztec defeat in the Battle of Tenochtitlan marked the beginning of the end for the Aztec Empire.

- Corn was the basis of the Aztec economy.

- Metalworking wasn’t very common in the Aztec Empire, except for the refining and working of gold.

- The Aztecs called their rulers Tlatoani.

- The first Tlatoani was Acamapichtli, who reigned from 1376 to 1395.

- The last Tlatoani was Cuauhtémoc, who reigned from 1520 to 1521.

Aztec Facts Infographics

The Aztecs didn’t call themselves by that name.

We may know them now as the Aztecs, but the term “Aztec” was simply a general classification for people who spoke the same language. Aztec translates to “People from Aztlan”, a region in Northern Mexico where they lived before migrating to Central Mexico.

Instead, the Aztecs referred to themselves as Mexica. It’s a religious term, based on a legend of how the god Huitzilopochtli renamed them upon their arrival in Central Mexico. The name’s shared with the people of the neighboring cities of Texcoco and Tlacopan. It’s also the origin of the name of the modern country of Mexico and its people, the Mexicans.

Nahuatl is the native language of the Aztecs.

Nahuatl refers to the Aztecs’ official language, dating back to the 7th century. Over time, Nahuatl changed with the Aztecs’ migration from Northern to Central Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. Today, Nahuatl remains spoken in Mexico’s rural areas. However, while this modern form is rooted in Classic Nahuatl, is no longer counted as the same language.

The Aztecs had their own alphabet.

Scholars and historians believe that Nahuatl writing is based on the older Zapotec alphabet. Unlike the Roman alphabet, Nahuatl writing doesn’t use letters corresponding to sounds or syllables. Instead, it uses pictograms to represent words or concepts.

Complex words, names, or concepts were expressed through combining two or more pictograms together. Unfortunately, only a limited selection of Nahuatl materials survived the Spanish Conquest. The Spaniards destroyed the government records and written cultural legacy of the Aztec people to ‘civilize’ the natives.

The Aztecs never called their domain the Aztec Empire.

The Aztecs called their empire the Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān or Triple Alliance. This alliance between the three city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan reigned the Aztec domain.

Usually, people visualize empires as that of Rome or China – with a strong central authority ruling over large territories along with military, trade, and foreign affairs. However, this wasn’t the case with the Aztecs. The Aztecs let their vassals govern themselves, and contented themselves with collecting tribute. Their vassals functioned independently with their own armies, trading with other nations on their own.

Tenochtitlan led the Aztec Empire.

Someone always has to be on top, and it’s no surprise that one city dominated the Aztec Empire. Though the Triple Alliance was equal on paper, Tenochtitlan dominated in practice.This is seen in the disparity between cities. At its height, Tenochtitlan was home to over 100,000 people. However, Texcoco only had a population of 45,000 people at most – with Tlacopan having an even smaller population.

Mexico City now stands on what was once the Aztec capital.

One of the little-known Aztec facts is that modern-day Mexico was built on Tenochtitlan, an Aztec city. Its name translated to prickly pear, referencing a legend where the god Huitzilopochtli told the Aztecs to build their city where an eagle holding a snake stood on a cactus. This symbol is also the Coat of Arms for the modern Mexican nation.

The Spaniards destroyed Tenochtitlan to build Mexico City.

The Spaniards recognized the central location of Tenochtitlan and decided it’d make a logical center for their new colonial empire in Central America. In order to make it their own, they destroyed it first – including the old temples, to remove any physical memory of the old religion.

After reducing the native city and their temples to ruins, the Spaniards built Mexico City on top. At the heart was a district reserved only for Europeans, with natives living around them. As the population grew, the Spaniards drained the surrounding lake and expanded the city onto the dry lakebed. A sad and unfortunate example of Aztec facts to be sure.

The Aztecs used a series of dams to control the waters around their capital.

As surprising as it might sound, Tenochtitlan was surrounded by Lake Texcoco – a saltwater lake. This led to problems when it came to supplying Tenochtitlan with freshwater. The Aztecs solved this with a series of dams that separated rainwater from lake water, gathering the rainwater for use in the city.

Those same dams allowed the Aztecs to manage the lake’s level, helping them build the artificial islands that surrounded Tenochtitlan. How’s that for cool Aztec facts?

There were 3 classes in Aztec society.

One of the sadder Aztec facts is that even in ancient times, the class divide persisted. Standing at the top of Aztec civilization was the pipiltin or the Aztec nobility. They accounted for around 5% of the total Aztec population. A majority of the Aztec people formed the macehualtin class.

At first, only farmers counted as macehualtin, but by the time of the Spanish Conquest, only 20% of macehualtin were farmers. The rest were warriors, merchants, and craftsmen. Finally, at the bottom of society were the tlacotin, or the slaves.

Aztec slavery was not like European slavery.

For one thing, Aztec slavery lacked the racist elements of European slavery. Slaves in Aztec society weren’t slaves because they were inferior – they became slaves as punishment for crimes or after becoming prisoners in war.

Other slaves traded away their freedom as part of an arrangement where they served in exchange for financial and livelihood support. Also unlike in Europe, slavery wasn’t hereditary. The children of slaves were free men and women, and slaves could earn money on the side, money they’d use to free themselves in time.

The basic organization of Aztec society was the calpulli.

Calpulli translates to “big house” in English. Scholars found it difficult to make a proper analogy with the calpulli in European society, though. Clans, towns, parishes, and even cooperatives all fit the calpulli’s role in some way, but not completely.

Leading each calpulli was the calpuleh, who managed the lands, settled conflicts, and collected tribute for their superiors.

The altepetl stood above the calpulli in Aztec society.

Altepetl translates to water-mountain in English. Unlike the calpulli, scholars found it easier to find an analogy for the altepetl: it functioned specifically as a city-state. Each altepetl ruled over a number of calpulli. A tlatoani ruled each altepetl. During the Aztec Empire, the tlatoani answered directly to the Mexica Emperor in Tenochtitlan.

The Aztec economy was quite advanced.

Despite what popular fiction says, Aztecs had no concept of money. Instead, the Aztec economy relied on barter, with goods and services traded in equivalent amounts for each other.

One standard used in trade was the quachtli, or a fixed length of cotton. Records indicate that 20 quachtli was the annual standard for a commoner living in Tenochtitlan. Agricultural goods were also among the less common goods traded. In contrast, manufactures like cloth, pottery, jewelry and metalwork were more common.

Aztec merchants formed exclusive guilds.

The Aztec pochteca, made a living going from one end of the empire to another. They bought and exchanged goods, services, and information with them wherever they went and supervised the markets of the Aztec Empire.

The Aztecs had two kinds of markets.

Some markets exclusively traded only one kind of product, such as corn or dogs. Other markets traded all kinds of goods and services. Regardless of the kind, all markets had supervision to ensure customers weren’t cheated, and to maintain standards. Strict punishments such as fines or worse awaited those who flouted the markets’ supervisors.

The Aztec civilization relied heavily on agriculture.

One of the Aztec facts that still apply to the present is that agriculture is important to every civilization. However, the Aztecs stood out for their very advanced understanding of agricultural science and engineering. Even before the rise of the Aztec Empire, they already started using terraces for farming to adapt to the hilly and mountainous lands of Mexico. This also allowed them utilize their limited water supplies efficiently.

Later on, the Aztecs developed advanced irrigation systems, with a complex network of canals and diverted streams and rivers to provide water for their crops. The Aztecs also innovated through artificial islands called chinampas to grow crops on top of lakes and other bodies of water. Even today, the Aztecs’ descendants still use chinampas to grow crops on.

All Aztec men received military training.

In the Aztec civilization, military training started at the age of 15. However, the Aztecs weren’t a warrior society like the Spartans of Greece. Most of the men didn’t become full-time warriors and only received basic training before returning to normal life. This mandatory military training only ensured that Aztecs would be ready for battle if the need ever arised.

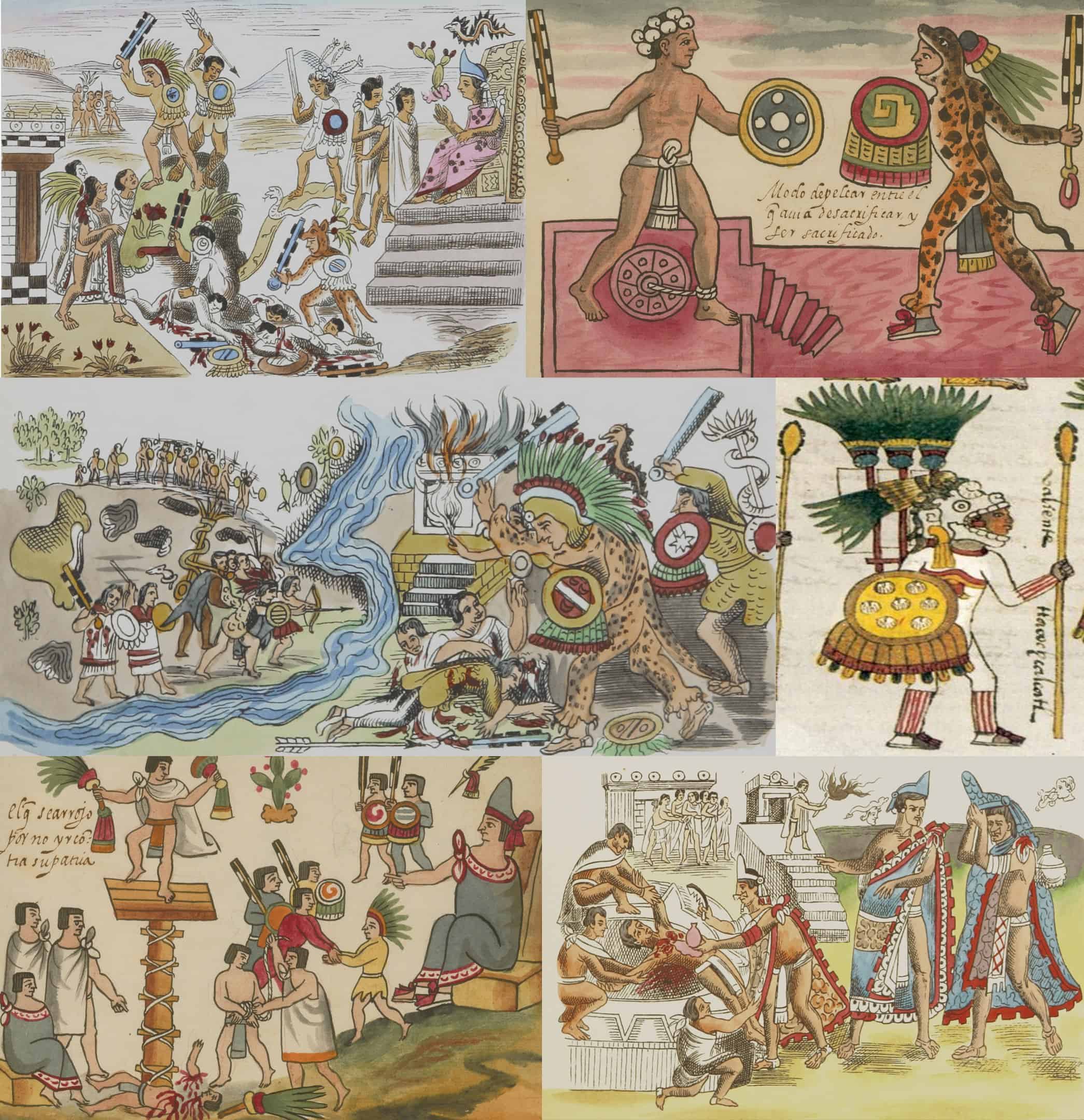

The goal of Aztec warriors in battle wasn’t to kill but to capture as many prisoners as possible.

These prisoners would get sacrificed to the war god Huitzilopochtli. The more prisoners a warrior captured, the faster they got promoted up the ranks. Definitely one of the darker Aztec facts.

The most elite of the Aztec warriors were the Jaguar Knights and Eagle Warriors.

The names sound like caricatures, but they’re actual translations of the terms Ocēlōmeh and Cuāuhmeh. Jaguar Knights and Eagle Warriors were similar to the knights of Europe, or the samurai of Japan. They all had their own unique codes of honor and held an elite position not only within the military but in society as a whole.

The Jaguar Knights and Eagle Warriors accepted members from all classes of society, not only the nobility. Skill and achievement was the only way to become one of them, even if an aspirant was a commoner. How’s that for neat Aztec facts?

The Flower Wars were a unique tradition from the height of the Aztec Empire.

The name is a misleading one, contributing to the misconception that the reign of the Aztec Empire was a chaotic and bloody time. The Flower Wars were ritual battles, between warriors from different city-states, and closer to tournaments than actual fighting. However, the end goal was still to to capture prisoners for sacrifice to the god of war, Huitzilopochtli.

The Aztecs had 4 main gods.

The most important was Huitzilopochtli (Left-Handed Hummingbird), god of the Sun and of war. After him were Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, and Quetzalcoatl. Tlaloc (One That Lies On the Land) was the god of rain and water. Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror) was the god of magic, night, and divine protector of slaves.

Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent) was the god of the wind and the sky, and the giver of knowledge and father of civilization. Even after the fall of the Aztec empire, Quetzalcoatl remained popular around the world.

Aztec sacrifices weren’t forced.

Popular fiction gives the impression that the Aztecs dragged slaves and victims screaming and struggling to the altar. However, this is only the product of a centuries-long propaganda by the Roman Catholic Church that demonized Aztec religion.

In reality, those chosen as sacrifices saw it as a great honor and ascended the steps of the pyramids proudly of their own free will. While their families mourned their deaths, they also celebrated their sacrifice knowing that the gods had already welcomed them to a glorious afterlife.

The Aztecs weren't the only ones who practiced human sacrifice.

Other Native American civilizations shared this aspect of Aztec religion. To the Aztecs, the sacrifices kept the Sun moving across the sky. If there weren’t any sacrifices, then the Sun wouldn’t move, destroying the Earth with eternal heat and daylight. The Aztecs’ sacrifices kept the Sun moving, but the gods also spilled their own blood as fuel for the Sun to keep shining.

A similar legend is how human sacrifices grant Huitzilopochtli, Quetzalcoatl, and Tezcatlipoca the strength to hold back the Tzitzimitl or the demons of the stars. If the gods fail to hold these entities back, they would destroy the whole world.

The Aztecs didn’t offer human sacrifices to Quetzalcoatl.

Quetzalcoatl was the only Aztec god that didn’t demand human sacrifices. The ancient Aztecs sacrificed butterflies and hummingbirds to him instead. According to legend, Quetzalcoatl also tried to convince the other gods to stop demanding human sacrifices.

This led to an argument after which the god Tezcatlipoca tricked a drunk Quetzalcoatl into sleeping with his sister Quetzalpetlatl. As penance, Quetzalcoatl exiled himself to the east but promised to return.

The prophecy of Quetzalcoatl was once thought to have played a role in the Aztecs’ downfall.

A common misconception is that the last Mexica Emperor, Moctezuma II, believed that Hernan Cortez was Quetzalcoatl returned. Allegedly, this made him welcome Cortez and delay the defense of the empire.

However, Cortez only lied about this propaganda to make himself more relevant and divert blame from the Spaniards. Scholars have since discovered that Moctezuma II or any of the Aztecs never believed that Cortez was Quetzalcoatl.

Another important Aztec god was Xipe Totec.

Xipe Totec was the god of agriculture, life, death, and rebirth. His name means Flayed Lord, a reference to his preferred method of receiving human sacrifices. When offering a sacrifice to Xipe Totec, priests flayed a virgin boy or girl and wore their skin for the next 20 days.

At the end of those 20 days, the priests placed the rotting skin in a jar, which was then put under the Pyramid of Xipe Totec. Corn was the Aztec’s staple food, and the flaying of the sacrifices symbolized how corn needed its skin removed before getting eaten. The sacrifices also symbolized Xipe Totec casting off the remains of the previous year and accepting a new life for a new year. Still pretty dark in terms of Aztec facts, though.

Tlaloc demanded child sacrifices.

Yes, it’s a rather disturbing example of Aztec facts. The children either came from the slaves, or from the younger children of nobility. Unlike other gods, Tlaloc’s holy places weren’t atop pyramids, but on top of the mountains.

There, the children had their hearts removed, and their bodies buried in caves with seeds placed in their mouths. If the children cried on the way to the caves, the priests considered it a good omen for the future.

It is unknown how many people the Aztecs sacrificed per year.

Sources from the Spanish Conquest once claimed that the Aztecs sacrificed over 80,000 people in only 4 days. Another source dating back to 1977 claimed that tje Aztecs sacrificed as many as 250,000 people per year. However, this has long been contested by Mexican scholars who argued that the Aztecs only sacrificed around 20,000 per year.

Evidence discovered in 2003 supports this, with the largest skull rack for sacrifices found not holding even a thousand skulls. Indeed, they argue that the Aztecs may have exaggerated the public records of the number of sacrifices to intimidate their enemies.

Not all sacrifices were human.

The Aztecs actually reserved human sacrifices for important occasions and feast days. On regular days, they sacrificed animals like dogs, eagles, deer, and even jaguars on most religious services. Sometimes, the Aztecs would offer their blood as a sacrifice instead. Art, gold, jewelry, and food were other alternatives to offer their gods.

The Templo Mayor was the most important temple in the Aztec Empire.

The Huēyi Teōcalli translates to the Greater Temple in Spanish. Archaeological studies indicate that the temple was rebuilt six times. The first time was around 1325, at the founding of Tenochtitlan. This temple was a simple one, made from earth and wood.

The final temple witnessed by Cortez in 1519 towered 60 meters above the ground, made from stone and finished stucco and polychromatic paint. The pyramid wasn’t only tall either, but massive as well, covering an area of 8 km². At the top were 2 shrines, one each dedicated to Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli.

The Templo Mayor was only the centerpiece of Tenochtitlan’s temple precinct.

The Templo Mayor was surrounded by 78 other buildings in the precinct. A protective wall called the Serpent Wall surrounded these structures. The temple precinct also included a residence for the Eagle Warriors and a school, for future priests.

The greatest temple short of the Templo Mayor was the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, located to the west of the precinct. This pyramid had a unique circular base. The pyramid was positioned so that during the equinox, the rising Sun’s light shone between the shrines of the Templo Mayor onto the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent.

There was only one other place holier to the Aztecs outside of Tenochtitlan.

This was Teotihuacan, a ruined city about 40 km to the northeast of what is now Mexico City. The city dates back to 1st century BC and finally fell into ruins between the 7th and 8th centuries AD. The builders and inhabitants of the city are unknown to this day.

As for the Aztecs, they saw the ruins as a place where the gods once dwelt on Earth.. The name reflects this, as Teotihuacan translates to the Place of the Gods. This place was so holy to them that they dared neither to rebuild nor settle the ruins.

The Aztecs believed four worlds existed before our own.

Tezcatlipoca ruled the first world, lit by the Jaguar Sun. Inhabited by giants, this world ended after Quetzalcoatl defeated Tezcatlipoca, who then ate the world out of spite. Quetzalcoatl ruled the second world, lit by the Wind Sun. Inhabited by the first humans, this world ended after Tezcatlipoca defeated Quetzalcoatl. His defeat caused a hurricane that destroyed the world and turned the surviving humans into monkeys. Tlaloc ruled over the third world, lit by the Rain Sun.

This world ended when Tezcatlipoca seduced Tlaloc’s wife Xochiquetzal, after which Tlaloc refused to let it rain. Quetzalcoatl then defeated Tlaloc to make him give rain, only Tlaloc rained fire instead of water. The surviving humans of this world became the birds. Chalchiuhtlicue ruled over the fourth world, lit by the Water Sun. Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca defeated her, causing a flood that destroyed the world. The surviving humans became the fish.

The Aztecs believed that we live in the Fifth World.

Tezcatlipoca lured the monster Cipactli with his foot, and killed it with Quetzalcoatl. Then they used its body to make new land amidst the waters that destroyed the fourth world.

Quetzalcoatl made the humans of the fifth world.

After making the fifth world, Quetzalcoatl and his spirit twin Xolotl traveled to the underworld. There, Quetzalcoatl convinced Mictlantecuhtli to show him the bones of the dead after playing a song with a flute. After seeing the bones, Quetzalcoatl had Xolotl make a distraction, while he took the bones with him back to the land of the living.

This trapped Xolotl in the underworld, where he serves as a guide to the newly-arrived dead. Upon his return, Quetzalcoatl ground up the bones of the dead, mixing it with his blood and planting it into the earth. From there came the first humans of the fifth world.

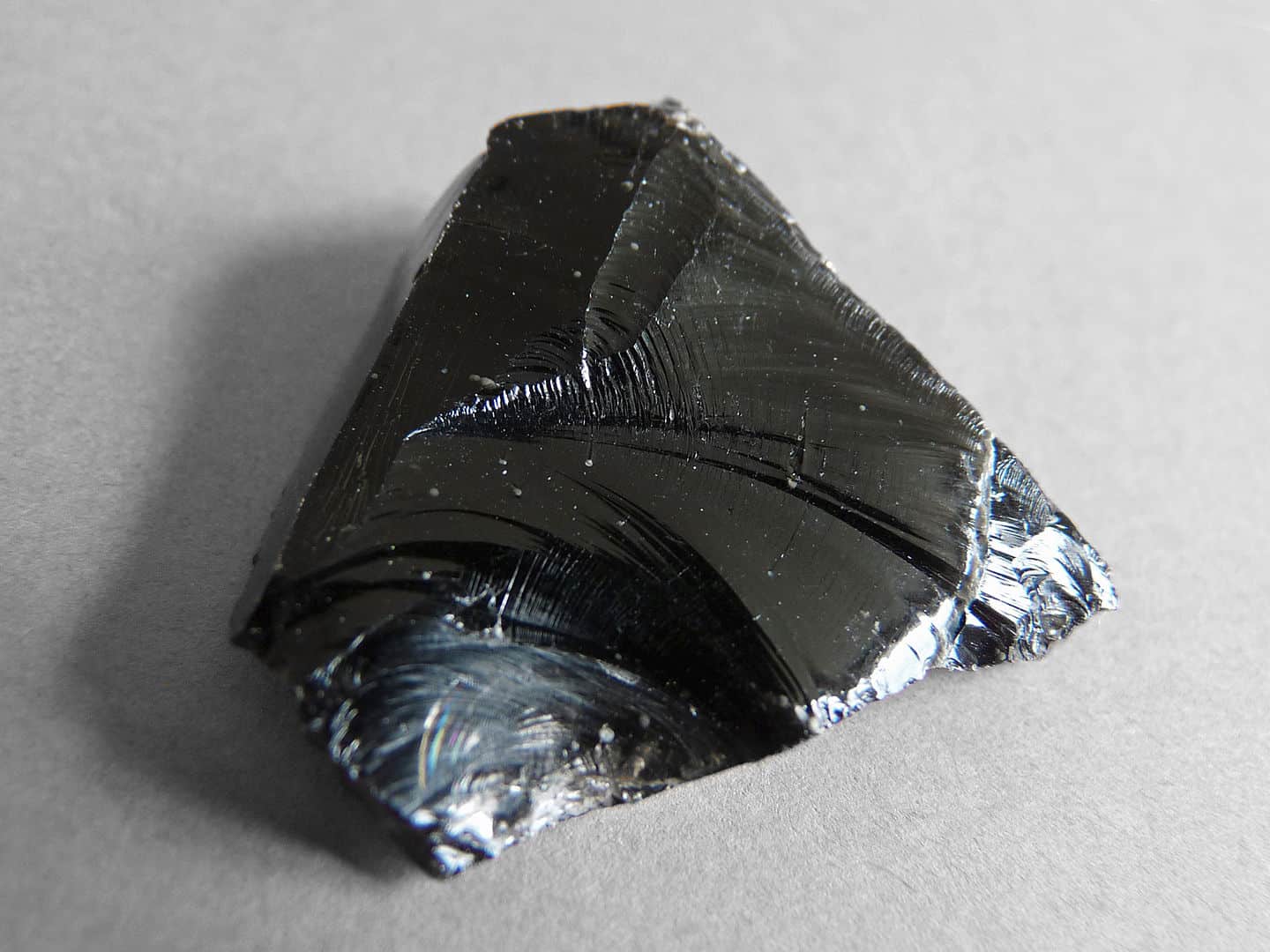

The Aztecs used obsidian instead of iron.

Obsidian is volcanic glass, usually black in color. The Aztecs used them as mirrors and as decoration, or cut and sharpened them as blades for weapons. While they knew plenty about refining and working with gold, and to a lesser extent copper as well, their knowledge of refining and working with iron was nonexistent. Obsidian made a perfect substitute, as sharpened obsidian is actually sharper than metal blades.

According to the Spaniards, an obsidian-bladed Aztec axe was sharp enough to cut a horse in two with a single blow, something their steel swords couldn’t do. However, obsidian is brittle and thus ineffective against the steel armor of the Spaniards. The glass shattered before biting through, whereas the duller but sturdier swords of the Spaniards had no problem with the lightly-armored Aztec warriors. Thus, the Spaniards managed to defeat them in battle. Talk about sharp Aztec facts.

The macuahuitl was the iconic weapon of the Aztecs.

The Maya, Mixtec, and the Toltecs all had their own variants of the macuahuitl. It has no direct counterpart in European weapons, bearing similarities to both maces and axes. Its name means hand-wood, referring to the weapon’s core, which was often a solid, paddle-like piece of wood.

The head’s edges were lined with obsidian carved into prism-like blades. These blades are easy to replace, as the Aztecs knew of obsidian’s relative fragility. Despite that, the macuahuitl was a dangerous weapon in the hands of a skilled user.

The Aztecs’ burial customs depended on the dead’s means in life.

Wealthy people, whether nobles or commoners, tended to burn the bodies of their dead. In contrast, the poor buried their dead under their houses out of practicality. This was also so they could continue to have a connection with their living family. Dead kings had a red dog sacrificed to accompany them into the afterlife.

The Aztecs understood the wheel mechanism.

The strange thing about this example of Aztec facts that Aztecs never used wheels. Rollers made from logs to move stones for their pyramids were the closest the Aztecs came to using wheels. That, and children’s toys.

Scientists think this is because of the mountainous land the Aztecs lived in that would’ve rendered wheels useless. The of rivers and bodies of water surrounding the area could also be a factor. The Aztecs preferred to use boats to move cargo on water, while hand-carrying cargo was faster and more convenient on land.

The Aztecs had public education.

Children started learning from their parents at home. They visited temples at regular intervals, during which they’d take tests to measure their progress. At the age of 15, they chose to attend one of 2 kinds of schools. The telpochcalli focused on practical and military studies and favored by the commoners for that reason. Boys who became warriors had more opportunities to advance in society. Girls or boys that didn’t become warriors learned handicrafts at the telpochcalli, all valuable skills in Aztec society.

The other kind of school was the calmecac, which taught abstract fields such as astronomy, statesmanship, and theology among other fields. This led the nobility to favor the calmecac, as they were better suited to teach future leaders. That said, there were no class restrictions in education. Commoners attended the calmecac if they chose to, while nobles attended telpochcalli if they chose to as well.

Chocolate was a delicacy in the Aztec Empire.

Legend claims that chocolate was one of the gods’ treasures until Quetzalcoatl shared it with man. The Aztecs couldn’t grow cocoa beans, so instead, they demanded it as tribute from those countries and cities which could. In fact, cocoa beans were a trade standard for the Aztecs, second only to the quachtli, and it was preferred for small transactions.

Records indicate 20 beans were enough to buy a small rabbit, and a turkey egg for 3 beans. Aztecs drank cocoa cold as a treat after dinner. However they used chili or vanilla beans instead of sugar. Chocolate was also part of rations provided to soldiers of the empire and was also seen as an aphrodisiac. It was from the Aztecs that the Spaniards learned of chocolate, who then introduced it to Europe. Now there’s a sweet example of Aztec facts.

The Aztecs had their own kind of basketball.

They called it ullamaliztli and used their hips and forearms to pass a rubber ball back and forth between players. The goal was to put the ball through a stone hoop in a wall, which merited a score. While a popular pastime, it also had religious connotations.

Aztecs played ullamaliztli during festivals, as part of celebrations that involved human sacrifices. Today, a form of the game called ulama is still played in parts of the countryside.

Aztec women enjoyed more rights than European women of the time.

There’s a brighter and very admirable example of Aztec facts. For one thing, both sons and daughters inherited equally from their parents. In Europe, daughters only inherited if their parents had no sons, and they weren’t bypassed by their parents passing on their properties to the daughters’ husbands. Aztec women also owned property independent of their husbands and made their own money off them.

The Aztecs practiced polygamy.

The practice was more common among the nobility than among the commoners. Some sources even claim commoners weren’t allowed to have more than one wife, but this is a claim that’s still debated today. Whether among nobles or commoners though, the first wife usually ranked above the ones following her.

The Spaniards greatest weapon against the Aztecs was disease.

They didn’t even do it deliberately. They brought diseases with them and spread it by simply interacting with the natives. The deadliest of these diseases were measles, mumps, and smallpox. The Aztecs had never encountered these diseases before, and thus had no resistance to them. In less than a year after the Spaniards came, 40% of Tenochtitlan’s population died from smallpox alone. Definitely one of the more unfortunate Aztec facts.

The Spaniards didn't defeat the Aztecs on their own.

Cortez and his conquistadores consisted of only 100 men. As such, it seems unthinkable that they succeeded in bringing down an empire with a population in the tens of millions. However, the hundred-or-so Spaniards managed to get help from Aztec-opposing cities like Tlaxcala.

With their help, the Spaniards succeeded in bringing the Aztec Empire down. While some historians argue that these cities opposed the Aztecs for their demands of human sacrifice, they soon came to regret their aid. The Spaniards didn’t demand sacrifices, but they demanded labor of gold and silver mines and treated the natives as inferiors.

An Aztec woman named Malintzin personally helped Cortez in his conquest.

Also known as La Malinche, she served Cortez as an interpreter and helped convince the Aztecs’ tributaries to side with Cortez instead. Scholars consider her contributions as beyond question in ensuring a quick and complete Spanish conquest.

After Mexico gained independence in the early-19th century, nationalists and scholars denounced La Malinche as a traitor who sold out her people to the Spaniards. Her name even became the root for malinchismo or malinchista – Mexican insults for those who abandon their culture for a foreign one. In the 20th century, feminists defended La Malinche, saying she only did the best she could in her situation, and argued that she became the mother of a new, Mexican people. The controversy over La Malinche’s reputation continues to this day.

Scientists named a dinosaur after Quetzalcoatl.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi is a pterosaur that lived over 68 million years ago. It stood about 3 meters tall, and between 11 to 12 meters wide with its wings spread. To put it into context, Quetzalcoatlus was as big as a small airplane. This makes Quetzalcoatlus one of the biggest flying animals to ever exist. We’re sure the Aztecs would have approved, as we see it here, at Aztec Facts.

The Aztecs had a 52-year religious cycle.

At the end of each cycle, each household broke their pottery and put out all their fires. In the Templo Mayor, a fire is then lit in the chest cavity of a sacrificial victim. This fire is then shared to the households of Tenochtitlan, and by runners to the surrounding communities. The Aztecs called this Xiuhmolpilli or the New Fire Ceremony. Now there’s a curious example of Aztec facts.

Aztec pottery changed over time.

This isn’t really surprising, as times change and with it people’s tastes. Archaeologists determine four phases in the development of Aztec pottery. The first and second phases overlap from 1100 to 1350. The first phase had the characteristics of floral design and symbols for each day in the Aztec week.

The second phase had the characteristics of grass-styled design and calligraphic markings. The third phase lasted from 1350 to 1520, during the rise, height, and fall of the Aztec Empire. The characteristic of this phase was surprisingly-simple line designs. The fourth phase was during the early colonial period, characterized by European influences on third phase designs.

One of the most prized art forms in Aztec society was feather working.

One of Aztec civilization’s most distinct crafts was using bird feathers to make mosaics and other art forms. In fact, they valued it so much that the importing of feathers (especially exotic ones) became a major part of the Aztec economy. One of the few surviving Aztec written materials is even an instruction manual for feather working.

Aztec music had several genres.

One was yaocuicatl, which were war songs sung by warriors to honor the gods. Another genre was the teocuicatl, or hymns to praise and honor the gods. Xochicuicatl referred to poetic music, while tlahtolli referred to prose in musical form.

Aztec warriors served under the Spaniards after the Fall of Tenochtitlan.

They served as auxiliary troops and bulked up the Spanish forces’ limited numbers of European soldiers. As a reward for their service, the Spaniards allowed them to found new settlements in conquered territories. This ensured that Aztec culture and the Nahuatl language, even if influenced by the Spanish, continued to spread for decades even after the fall of the Aztec Empire.

Many Aztec governors continued to govern under the Spaniards.

The only difference was that they no longer served the Mexica Emperor, but the Spaniards’ new Viceroy of Mexico. This also ensured the Spaniards did not have to rebuild the social and governing structure as a whole and only make adjustments in line with their vision of a Christian and Spanish Mexico. While some of the native governors later lost their positions, others grew rich and powerful under Spanish rule.

Aztec nobles who submitted enjoyed good treatment under the Spaniards.

After the fall of the empire, the Spaniards demanded the Aztec nobility to convert and swear allegiance to the Spanish crown. Those that did receive titles from the King of Spain, and recognition as members of the Spanish nobility. This included Moctezuma II’s great-grandson, who became the Count of Moctezuma.

One of them even became Viceroy of Mexico from 1696 to 1701, José Sarmiento de Valladares, and later received the additional title of Duke of Atrisco. The title of Count of Moctezuma remains recognized by the Kingdom of Spain to this day.

Mexican independence saw a revival of interest in Aztec culture and history.

Before Mexico’s independence, the demonizing of the Aztecs as barbarian savages was common. However, this changed with its independence as the Mexicans looked back on their past identity as a nation. Scholars gathered Aztec writings and artifacts, using them to piece together the Aztecs’ culture and history and to remove the falsifications of colonial rule. It was at this time that the ancient symbol of Tenochtitlan, the eagle eating a snake on a cactus, became the coat of arms of the Mexican nation.

Early modern Mexican history saw controversy over studies of the Aztec past.

The controversy was between Mexican conservatives and liberals. The conservatives rejected the notion of a glorious, pre-Hispanic past, preferring the idea of a Catholic, European Mexico.

In contrast, the liberals embraced the Aztec past, and while not rejecting the contributions of the Church and Spain to Mexico, refused to ignore the Spaniards’ crimes. It was not until 1854 and the downfall of conservative leader Santa Anna that the liberals emerged victoriously, and Mexico embraced in full its Aztec past.

Mexican President Porfirio Diaz sponsored archaeological studies of the Aztecs.

Diaz was the President of Mexico from 1876 to 1911, and while his economic policies remain controversial to this day, he’s also remembered for his support for studies of the Aztec past. Archaeologists and scholars received ample funds to study and look for Aztec artifacts and remains. Diaz also sponsored the protection of monuments dating back to Aztec times.

Mexican President Porfirio Diaz raised a monument to Cuauhtémoc in 1887.

Designed by Francisco Jiménez, Ramón Agea, and Miguel Noreña, it’s built in honor of Cuauhtémoc, the last tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, and a cousin of Moctezuma II. Construction began in 1878 and finished in 1887. The monument stands 4.93 meters high, on top of a pedestal 11.75 meters high. Talk about honoring the past, as we see it here at Aztec Facts.

Several food items use names derived from or transliterated from their Aztec name.

It’s without doubt at Aztec Facts that the Aztecs contributed many things to world cuisine. Chocolate, for example, comes from xocolatl. Another example is the tomato, which in Nahuatl is tomatl. Chili in Nahuatl is chilli, while avocado is ahuacatl. Taco is tlaco in Nahuatl, while tamale is tamalli, chipotle is chilpoctli, pozole is pozolli, and atole is atolli.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.